Oxford United Football Club’s new 16,000-capacity stadium will be the country’s first mid-sized all-electric football venue. Mott MacDonald’s Steve Mills explains what went into designing this landmark project and what the sector can learn from it.

Planning approval of any stadium is exciting news for sports fans, but when Oxford United Football Club achieved that milestone this summer, it was also an electrifying moment for the construction industry.

As well as creating a new stadium for the club along with a 180-bed hotel, gym, restaurant and conference and event facilities, it is set to become the UK’s first mid-sized all-electric stadium too.

The brief from the club in 2023 was to design a larger, permanent home for the team that was also the most sustainable mid-sized sports venue in the UK. However, there is much that designers of other types of buildings can learn from the approach taken by the design team behind the project.

Mott MacDonald led on engineering services for the new stadium and worked in a collaborative design team with Ridge + Partners, AFL Architects and Fabrik Landscape Architects.

Reduction in CO2 emissions

Key to the all-electric design is the use of air-source heat pumps which, when combined with an energy-efficient building fabric, remove the need for carbon-based fuels and result in an 80% reduction in CO2 emissions per year compared with gas boilers.

The stadium will also have 3,000 sq m of roof-mounted photovoltaic (PV) panels helping to reduce the impact on the national grid, with in-built potential for future PV array expansion.

While the building’s low-carbon emissions are a positive for the environment, the team had to work hard to ensure the operational costs did not detract from the all-electric approach. While greater use of electrification is more carbon-efficient and is the direction of travel for regulation, electricity prices are significantly higher than gas.

The current ‘spark gap’ between the two meant that advanced modelling was essential to achieve reduced peak energy demand while also demonstrating regulatory compliance.

Virtual environment analysis

Design of the new football stadium was undertaken using IES Virtual Environment software from RIBA Stage 2 onwards to measure design outputs. The software also facilitated an iterative process to optimise solutions for the high-quality specification needed to meet the club’s aspirational sustainability targets. In addition, the software was critical to demonstrating the design’s compliance with building regulations.

The model created using the IES software took into account weather associated with its real-world location, geometrical size and form, occupancy patterns and usage types. This provided a highly accurate output of many variables relating to the forecast building use, including energy consumption and associated carbon emissions.

The IES Virtual Environment tool – and other similar thermal analysis software – can provide very detailed information to help assess solutions, analyse options for changes to improve results and, ultimately, provide an optimised output.

Digital twins can also create highly accurate building estimates for operational use during the design phase. Once in operation, they can be used with live monitoring and create interventions if the operational building’s energy use does not match the expectations set at the design stage.

For larger and more complex projects, software such as Hysopt can be used to further optimise system sizing and operation to reduce plant size – in terms of cost and space – to improve efficiency, capital cost and operating cost.

Increasing levels of detail

Use of these types of tools is essential to aid optimisation, such as balancing “fabric-first” changes with the operational phase, as taking a leaner approach to the design might reduce embodied carbon, but may result in a higher level of operational carbon. This approach considers the embodied carbon of designs that use more building fabric against optimised system operating temperatures – where systems become more efficient at lower operating temperatures – to maximise efficiency.

The fact that the tools are very complex means the levels of input needed can be significant. It is therefore easy to spend a lot of time in the early stages building a very detailed model, only for it to change as a project’s content is developed. The key lesson is to gradually increase levels of detail through RIBA Stages 2 (Concept Design), 3 (Developed Design) and 4 (Technical Design).

Designers should also bear in mind that while tools provide more granularity in terms of building performance, their use must be accompanied by a positive change in design mindset. This change in thinking is vital to move away from “what’s been done before” and find the right solution for each building that delivers benefits for both construction and operation.

Design changes for Oxford United

In addition to the air-source heat pumps and solar power, this iterative optimisation process for the Oxford United stadium also resulted in the adoption of low energy lighting with automated occupancy and daylight controls, as well as occupancy-led heating, ventilation and cooling control strategies throughout.

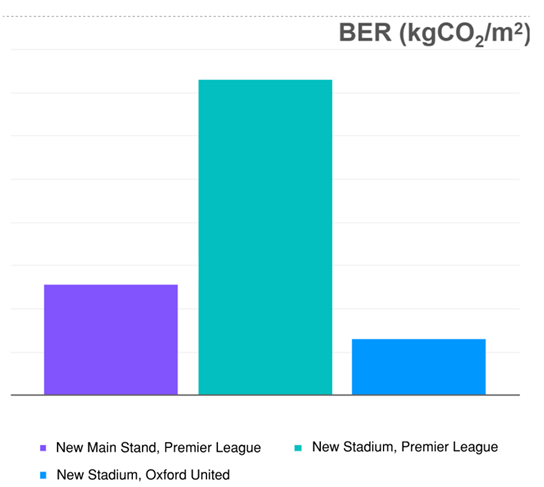

The analysis has shown that the completed stadium is expected to have a target emission rate – the overall carbon emission per square metre – around 25% lower than the equivalent value for other recent mid-large-scale all-stadia projects in the UK. This is a direct result of the energy efficiency and renewable energy measures employed.

The design team also expects that the building energy rating – its energy efficiency – for the stadium will be more than 75% lower than a large-scale stadium complex heated by a gas-fired solution.

The focus on sustainability goes beyond the operational carbon and aims to also reduce the embodied carbon through design changes. The structural design incorporates lean structural frames with a timber roof into the design to help minimise the building’s embodied carbon. Sustainable drainage and earthworks solutions have also been designed to work in harmony with the site ecology and environment.

Going all-electric clearly has carbon benefits, but the building cannot be designed in isolation. Where the power for it comes from is also key. In the UK generally, delays and waiting times for grid connections can block many projects, with developers forced to pay for local upgrades or wait for systems to be built before progressing with their own development.

Designing in onsite renewables is critical to the success of an all-electric design. For Oxford United’s stadium, this challenge was resolved by integrating the roof-mounted photovoltaic panels into the design.

New build must lead the way

As the government is working to decarbonise the electricity network in the UK, it is also critical for more buildings in the UK to be adapted to all-electric use to meet the 2050 carbon net-zero target.

However, it can be complex to retrofit many existing buildings due to local constraints, which is why it is essential that designers of new buildings, where systems can be designed from scratch and the building optimised accordingly, focus on going all-electric.

To underline how critical this is: four out of five buildings that exist today will still be in use by 2050, so with the retrofit challenges, it places a burden on new builds to cut operational carbon. Retrofit projects should equally challenge the use of fossil fuels to contribute to reducing the operational carbon of existing buildings.

The work the project team has delivered for the design of Oxford United’s new stadium helps demonstrate that there are still challenges to be faced by new builds that go all-electric. These are not insurmountable, though, and through collaborative working, can be overcome and buildings developed that we can be proud of in 2050 and beyond.

Steve Mills is technical director for building services at Mott MacDonald.