Perched on the outside of the fast-rising One Leadenhall development, an unusual tower crane is speeding up construction on this new City office building. Kristina Smith reports.

From a distance, it looks as if it’s floating. A tower crane serving the One Leadenhall site in the City of London is growing out of the building’s partially erected steel frame. It’s a lovely bit of engineering. Designer Robert Bird Group’s goal was to improve construction sequences and shave time off the programme for client Brookfield Properties.

“It’s all about solving logistical problems,” says Matt Quilty, project director for Robert Bird. “Putting the crane here means you can accelerate the build because you are not having to work round it.”

Robert Bird Group is both the structural engineer and the temporary works engineer on this project. This means that, working with construction manager Multiplex, it can win multiple programme, cost and material gains by designing the permanent and temporary works in tandem.

With the busy Gracechurch Street running down one side of the plot, this is a typical tight City site. One Leadenhall, which replaces the seven-storey Leadenhall Court, will be far higher than its predecessor at 35 storeys. However, its design by Make Architects means the height is less obvious from street level: the first four storeys have a masonry block design to reflect the feel of adjacent streets, with a glass tower stepped back and rising up from that.

Central concrete floor

The steel frame of the 40,000 sq m office building, which will have some retail units on its ground floor as well as a fourth-floor viewing platform open to the public, has a central concrete core to provide stability. A composite floor wraps around the central core with columns located only at the building’s perimeter to provide an uninterrupted floor space. The corners of the building are column-free too, to maximise views for future tenants.

The plot is next to the Grade II*-listed Leadenhall Market, which is being closely monitored throughout the construction process. Whereas the old building had a one-storey basement, the new one has a two-storey one. Robert Bird’s design saw excavation of the new basement through the existing one, using the perimeter of the old basement floor as a waling beam to provide stability to during construction.

“We used a top-down construction sequence and reverse engineered the basement structure as it was originally designed, going back to the original drawings,” explains Quilty.

The 100 new piles for the basement, 30m long and dry bored, were designed to reach to the bottom of the London Clay and located to avoid the positions of the shorter piles which supported the previous building.

Robert Bird, which also carried out the geotechnical engineering for the project, chose dry piles because this avoided the need for a bentonite plant on site which would have used up precious floor space. Again, explains Quilty, the design sought to optimise working space for Multiplex so that all the activities could progress faster.

Where temporary and permanent combine

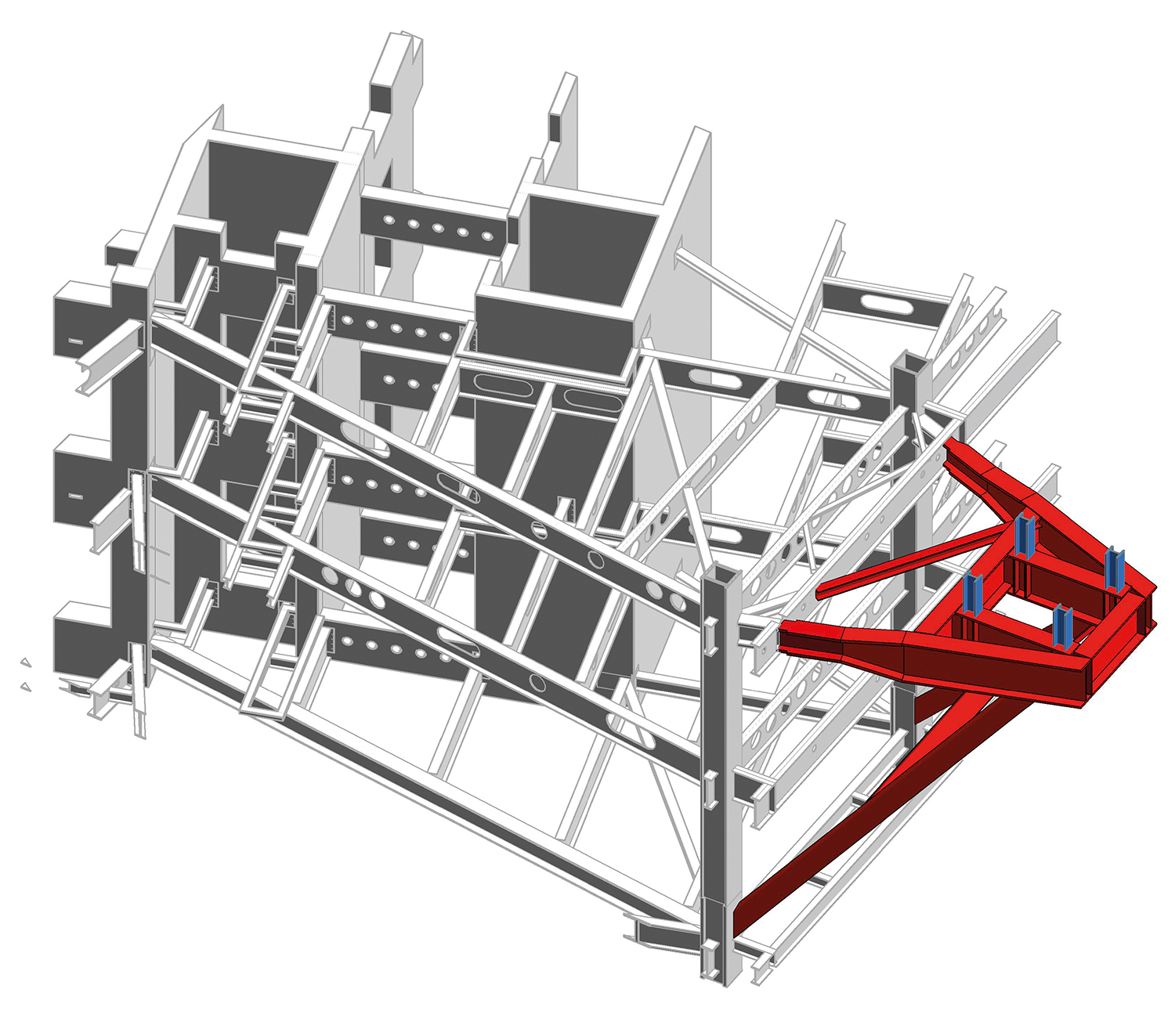

The tower crane on the outside of the building isn’t really floating. It sits on a bespoke steel H frame which is cantilevered off the steel frame of the building. Specialist contractor William Hare manufactured both the permanent and temporary steel and designed the fixings. The crane’s mast will tie into the building at levels 8, 17, 23 and 29.

“Since we are both the structural engineer and the construction engineer, we were able to integrate and enhance the permanent steel to take the additional forces in the temporary condition from the crane in the very early phases,” says Quilty.

“We’re not putting in temporary works – we are enhancing the beam by a small amount to make sure it can do two jobs: hold the floor in the permanent condition and the crane in the temporary condition. It is a much more sustainable way to build.”

Adding in temporary steel support work later could have had other knock-on effects too, says Quilty. The flanges of the floor beams have large holes in their webs for building services to pass though; additional beams could have interfered with that, for instance.

The trickiest thing about designing the grillage and crane system was making sure that it would not interfere with the facade, which has mullions every 1.5m. “We really had to think about where we put the ties,” says Quilty.

Construction tolerances

Robert Bird engineers also had to check all the deflections of the crane and the building and how they impacted on each other. “You have to be aware of the construction tolerances and the movements of the grillage which you are superimposing on the movements of the building,” says Quilty.

“If you are doing this type of bespoke system you need to work closely with the permanent engineer.” Which is easier when you work for the same company and are sharing the same model.

The crane, which is a Terex CTL 282-18 Luffing Jib Tower Crane, is currently 72m tall with a 25m jib. It has the capacity to go up to a 140m mast in its final phase with a working jib of 30m. It was erected with the help of one of the other two tower cranes on site, both of which are climbing cranes sitting within the building’s core.

Robert Bird, which has designed similar cranes for projects at 22 Bishopsgate and 100 Bishopsgate, was able to design the concrete core with shelves within it to support the climbing cranes.

“Every time we design a system like that, we improve it,” says Quilty.

All cranes are now hard at work, with the concrete core having reached level 24 by early June and the steel frame almost up to level 16.

One Leadenhall’s crane isn’t unique. Robert Bird designed a similar one for the Shard, back in 2009 – although that one was higher up, so not so noticeable from street level, says Quilty. However, it is a neat solution in a very tight working environment.