Can a heritage building be smart too? That’s the plan for the new Museum of London in London’s historic Smithfield market, opening in 2026 under the name of london Museum. Kristina Smith meets the client and Sir Robert McAlpine’s construction team.

The Museum of London has ambitious goals for its new facility at Smithfield market near Farringdon, home to the city’s meat markets over several centuries. It wants it to be the world’s smartest museum.

“It’s about building a new museum which is ready for the future, with the least environmental impact possible,” explains the museum’s technical lead, Steve Watson.

The smart building will collect data of every kind for AI algorithms to analyse, spotting glitches or faults or suggesting new ways to run systems more efficiently. “It provides the best chance for us to model, manage and control the environment, while emitting the least carbon possible,” says Watson. “I don’t think we can do that without building a smart building.”

Watson sees a time when individuals will be totting up their carbon footprints and planning trips accordingly. “Visitors will be making choices about what they do based on their carbon impact.”

Project overview

Value: £437m (London Museum project total)

Programme:

Sir Robert McAlpine appointed – May 2023

General Market building completion –

Q4 2025

Poultry Market building completion –

Q4 2026

Construction manager: Sir Robert McAlpine

Architects: Stanton Williams Associates, Asif Khan and Julian Harrap Architects

Structural engineer: AKT II

Building services: Arup

Cost management: Gardiner & Theobald

Contract: JCT Construction Management

In practice that means that all the operating systems, building services and technology will be heavily integrated, says Watson. “Typically, software systems that run our buildings are in silos. While that’s good for construction, when a building goes into operation, that’s a major problem.”

Overseeing that integration is Sir Robert McAlpine, appointed under a construction management contract to oversee the works from June 2023. “When we were choosing a construction manager, McAlpine had smart building experience and understood what our aspirations were. That gave us the best possible chance of developing an integrated building,” says Watson.

Pre-historic roots

The Museum of London – to be officially rebranded as the London Museum in July 2024 – tells the story of London from its pre-historic roots. Outgrowing its former 1970s-built home at London Wall, which the City of London Corporation has earmarked for redevelopment, it closed its doors there in December 2022.

Just half a mile away from London Wall, the museum’s new home will comprise a cluster of buildings in West Smithfield near Farringdon Station: the General Market, West Poultry Avenue, and the Poultry Market. Sir Robert McAlpine’s contract covers the General Market, built in 1883, and the 1960s Poultry Market building, which was reconstructed after a fire destroyed the original 1875 building in the 1950s.

The General Market has been out of use since the 1990s. The Grade II-listed Poultry Market only became vacant in August 2023 as its traders left – eventually to relocate to a new site in Dagenham.

The design team of Stanton Williams, Asif Khan and Julian Harrap Architects was picked via international competition back in 2016. Planning was approved by the City of London in 2020 and an updated application green-lighted in November 2022.

When Sir Robert McAlpine came on board, the rehabilitation work on the General Market was well underway. The museum had contracted Paye Stonework and Restoration in 2020 for a £12.5m contract which included the complete reroofing of the building, and Keltbray in 2021 for a £17.5m demolition and structural package.

Key suppliers

Structural steelwork (Poultry Market): Severfield Infrastructure

Facade and roof restoration (General Market): Paye Stonework and Restoration

Mechanical and electrical (General Market and Poultry Market): Phoenix ME

Ventilation (General Market and Poultry Market): Imperial Ductwork Services

Facade (General Market and Poultry Market): Seele (UK), West Leigh, Novum Structures

Historic shopfront and washroom fit out (General Market): JJ Sweeney

Demolition and concrete structure (General Market and Poultry Market): Keltbray Built Environment

In 2023, the museum’s contracts with Paye, Keltbray and others were converted to trade contracts to sit under McAlpine’s construction management contract. “This was a way to manage the project and line everything together,” says McAlpine project director Richard Hill.

“It means we can minimise future risk and maximise programme opportunities.” The museum had looked at the design-build route, rather than construction management, but it wasn’t viable for a project with this many uncertainties. “No one would take the risk,” says Hill.

Smart puzzle

The big puzzle for this project is not just how to accommodate the building services and systems among the existing, often irregular, fabric of the building. It is how to transfer the data relating to those elements into asset management software that will optimise the running of the museum.

Arup created the Museum of London’s smart building specification, including names for every single item of equipment, cabling and kit, based on the BDNS (Building Device Naming Standards) from the Open Data Institute.

“A key element is that we specify the asset naming conventions and that there is strict governance so that people stick to those conventions. This should happen as early as possible, preferably [RIBA] Stage 2,” says Watson.

These requirements were part of the tenders that McAlpine put out to the market. For the most part, its regular supply chain is up to speed with digital tools and protocols, says Irina Gales, senior digital construction manager for McAlpine. However, the smart building approach here is pioneering.

“We are pushing the boundaries with respect to smart buildings, workflow and data creation processes that are not yet industry standard,” says Gales. “We have established our own way of working, drawing on experience from our supply chain members and from the client.”

Watson is piloting his smart museum approach at the Museum of London’s other branch in Docklands. There, he is using the same master systems integrator as at Smithfield, One Sightsolutions, which he describes as “a kind of digital clerk of works who makes sure people are producing the right data with the right structures”.

“Once the data is in order you send it to a smart building platform,” he says. “We are using onPoint from a company called Buildings IOT.”

During the construction phase, the usual host of software packages are being deployed: Revit, Tekla, Inventor, HiCAD, AutoCAD 3D, SteelWorks, BIMcollab, Power BI, iConstruct, Dalux, Trimble Connect, Autodesk ReCap, Navisworks, Synchro, Solibri, Revizto, Autodesk Construction Cloud, Field View, Viewpoint and Edocuments.

Both Hill and Gales single out Dalux as a newer tool that is working well. “It offers a platform that is simple to use,” says Hill. “Where you federate the model so frequently, you might go into document management and look at a drawing which may not be up to date. With Dalux, you know that the information is common across everything.”

When introducing a new piece of software, Gales sits down with each person on the team to train them in a way that works for them. Next up is Buildots, which will help ensure all the services are in the right place.

“A lot of what we’re doing is bespoke and that’s where modelling and digital tools help,” says Hill. “Buildots will tell us when things are in and out of position. The tolerances are quite tight. That will help us because of the complexity of the building shape and the congestion of services within some spaces like the basement plant room and corridors.”

Out on site

The main entrance to the museum will be via West Poultry Avenue, which runs between the General Market and the Poultry Market buildings. Open from 7am to midnight, the avenue will have a new glass and zinc roof to replace its decayed roof structure.

Turning into the General Market, visitors will find the museum’s ‘Our Time’ exhibition. “This will be exhibits from living memory, from the past 80 years,” explains the Museum of London’s senior media officer Bree Wilkinson. “It will also be a social space with restaurants and shops. It’s like the front room of the museum.”

The basement of the General Market, ‘Past Time’, will contain the bulk of the museum’s historical exhibits. “The basement is at Roman street level, so it makes sense to have our Past Time material here,” says Wilkinson. This cool underground space – once home to stores for the markets – will help with energy efficiency too.

Currently, the General Market’s ground floor is just a shell. Everything inside has been stripped back, including the shops and offices which sat inside its perimeter walls. Wall coverings and fireplaces, incongruously sitting halfway up the inner walls, are all that remain now of these elements.

Although clear now, this area has been a forest of scaffolding, providing access and cover for Paye to replace the roof – which was complete by March 2024 when CM visited the site.

There is a huge amount of copper work on the General Market and the Poultry Market roofs. “The big copper dome pretty much used all the coppersmiths in the City, 10 or 12 of them,” says Hill. In a wonderful nod to the past, 83-year-old coppersmith Chris Johnson laid the final sheet on the Poultry Market’s roof – which he had helped install in the 1960s.

A new staircase between the ground floor and basement in the General Market has already been constructed, featuring layers of different coloured concrete, signalling the layers of city that have built up here over time. Deliveries once arrived by rail to the basement and the Thameslink train tunnel cuts through the site at this level; visitors will be able to watch it pass through a window in the basement’s wall.

Victorian brick vaults

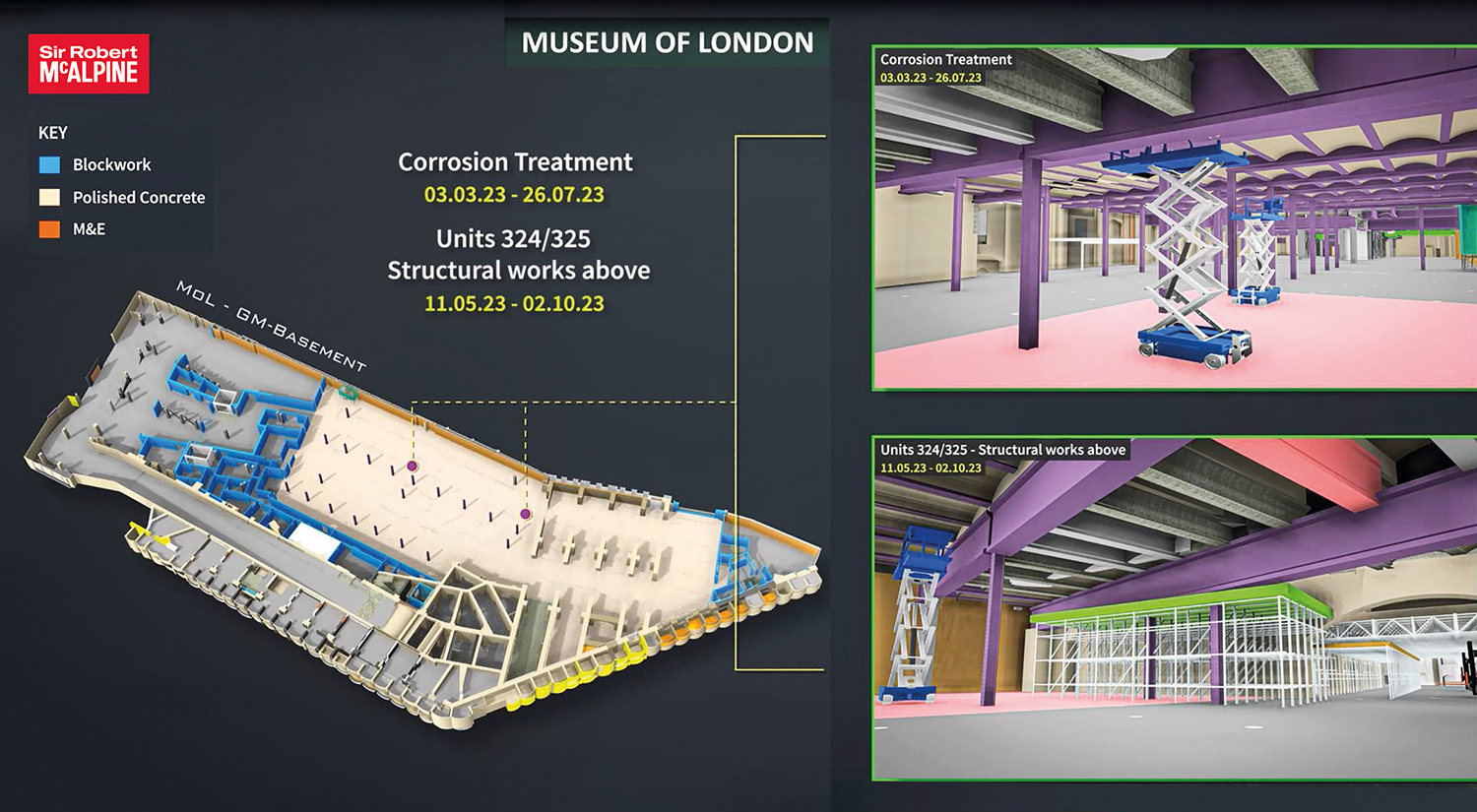

Keltbray’s works have included cleaning 10,000 sq m of Victorian brick vaults, and creating new service trenches and concreting the floor. Elsewhere, blockwork walls have been erected for plant rooms and back-of-house circulation corridors.

Inside the Poultry Market, as from above, the most striking feature is the concrete dome that spans the main central area. At 70m by 40m, this was the largest spanning concrete dome in Europe when built in the 1960s by McAlpine – and one of the main reasons for its listing.

This building will house ‘Deep Time’ in its basement – mostly stores for the museum. The ground floor will provide exhibition space alongside a learning centre for schools and other visitors. On level 1, accessible to the public, there will be office space and laboratories, with a perimeter walkway and a central area beneath the dome which will house temporary exhibitions.

Due to its listing, some elements of this building had to be logged before being taken off site for restoration or storage. Here Sir Robert McAlpine deployed a system of QR codes which it used on the restoration of Elizabeth Tower – better known as Big Ben – and other heritage projects.

Currently, there is some serious demolition underway to make way for a new internal structure, with a team of mini machines moving rubble around. Severfield will install a steel frame that extends up from the basement, tying into the existing structure at ground floor and level 1.

There is still some way to go on the project. Current plans see the General Market due to open in 2026, while the Poultry Market is scheduled to open in 2028. The Museum of London Docklands remains open.

As for whether visitors will know they are walking into a smart building, that’s less clear. But the data its systems are producing and munching will certainly become part of the museum’s sustainability story, aimed to attract London’s younger generations.

CV: Irina Gales, senior digital construction manager, Sir Robert McAlpine

As a teenager, Irina Gales wanted to be an architect. Originally from Romania, she studied architectural technology and construction management in Denmark, followed by an internship with a UK architectural practice as a BIM manager.

“Everything I had learned in Denmark was with digital tools. That’s the way the Nordics work,” she says, now a senior digital construction manager at Sir Robert McAlpine.

After her internship, Gales worked for various contractors on the Battersea Power Station, finishing phase three with Sir Robert McAlpine, moving to 21 Moorfields and then on to the Museum of London. She is enjoying being part of construction’s digital transition: “It’s a continuous learning curve. That’s what excites me.”

CV: Richard Hill, project director, Sir Robert McAlpine

Project director Richard Hill started working for Sir Robert McAlpine fresh out of university 25 years ago. “I am very lucky,” he says. “I get to work on fantastic projects.”

Hill appreciates the chance to leave something physical after the hard work of a construction project. “I walk around London, and I think, ‘I was involved in that one’. We are leaving this legacy for generations to come.”

It’s not so often that he can revisit the interiors of the buildings he has constructed. Offices such as Stanhope’s Gateway West and Gateway Central, which Hill worked on prior to this project, become private spaces. But he is looking forward to wandering round the Museum of London as a visitor in years to come.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Why rename the museum? ‘London Museum’ could mean anything, whereas ‘Museum of London’ is clearly specific as to its purpose.’If it ain’t broke….’!!