Adding tiny amounts of graphene to concrete promises big benefits in terms of performance, durability and carbon savings. Kristina Smith looks at the potential of this super-strength material.

“Graphene’s biggest challenge is it can offer something to almost every sector,” says Stephen Hodge, CEO of graphene producer Versarien.

Graphene-enhanced concrete is one of the applications that Versarien has decided to explore because of the pressing need to reduce the environmental impact of concrete, says Hodge.

It is not alone in its ambitions. Researchers and companies in the UK and overseas are working hard to create a viable graphene-based additive for concrete that will allow its deployment to be scaled up.

The proposition is that adding tiny amounts of graphene to concrete can improve multiple properties, such as compressive strength, flexural strength, impermeability and chloride migration. This would mean that concrete – and crucially Portland cement – can be used more efficiently and last longer, reducing the embodied carbon of structures.

There are several hurdles to clear, including the cost of graphene, the variability in quality of graphene and technical issues around dispersing it in the concrete. Exaggerated early claims of graphene-enhanced concrete’s performance have also caused concern among some investors. Estimates on the potential growth of the global market for graphene-based concrete additives vary, but all agree it is growing fast. A January 2025 report from Verified Market Research values the market at £15m in 2023 and projects it will rise to £123m by 2030.

Born in Manchester

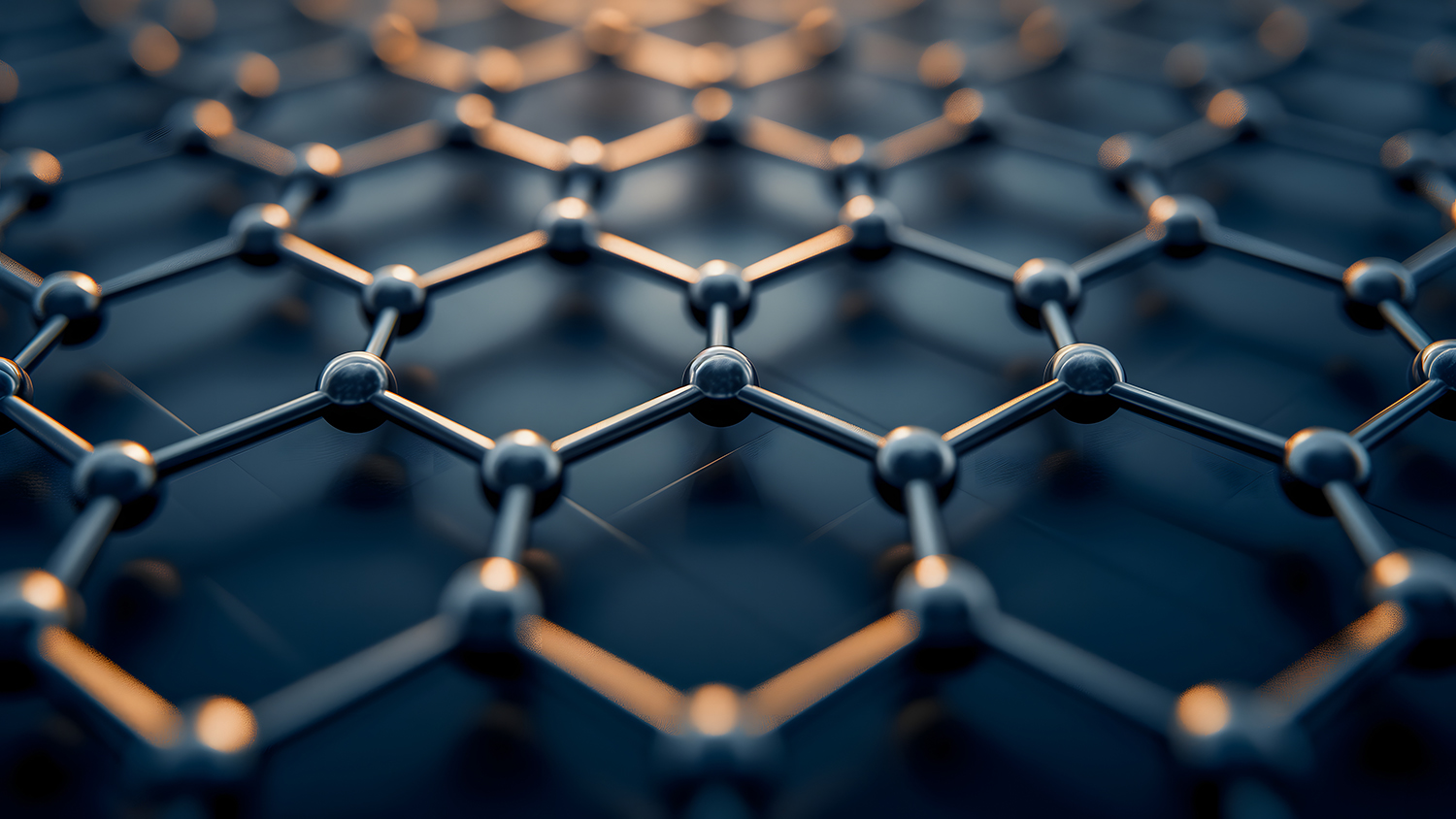

Graphene was discovered by researchers at the University of Manchester in 2004, a super-strong material that is just one atom thick. Its strength and thermal conductivity mean that its potential applications seem almost endless, with applications in electronics, composites and coatings, biomedicine, energy and sensors to name but a few. But there are many versions of graphene, explains Hodge, which are made from a variety of sources including waste materials such as methane and plastic.

“Graphene is not just one thing, it’s thousands of materials,” says Hodge. “Depending on the manufacturing process and the raw materials, the end product is different.”

Graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs), which consist of between three and 10 layers of graphene, are generally used in additives for concrete. These are less expensive to produce than the single-atom-thick graphene used in applications such as semiconductors.

Variability of graphene quality was an early challenge in producing graphene-enhanced admixtures, says Alan Beck, head of project management at Concretene, which was set up in 2022 to produce a graphene-enhanced concrete admixture of the same name. “With a novel material like graphene – which has highly variable methods of production – ensuring reliability and repeatability of performance from batch to batch is challenging.”

The cost of GNP has reduced significantly in recent years, says Beck, but the sector needs to see the same economies of scale that have been achieved for GNP produced for the polymer and coatings sectors. “Where small-batch GNPs were typically more than £500 per kg in 2020-21, we anticipate that graphene for use in concrete will have to be sold considerably below £50 per kg at scale to enable a price point that works for industry.”

One of the technical challenges in producing a graphene-enhanced additive that can be used like any other concrete admixture is how to disperse it evenly in concrete.

“Graphene doesn’t like water,” says Beck. “It’s extremely hydrophobic. And concrete is a water-based system, so you need a chemical formulation to disperse the graphene evenly in the cementitious system and let it do its work without agglomerating. Keeping the GNPs in a stable suspension is vital to performance and is something we’ve achieved this year with Gen 2.”

Graphene in action

From a performance perspective, graphene-enhanced concrete has demonstrated its potential in the UK. A prototype of the Concretene additive was developed by the Graphene Engineering Innovation Centre at Manchester University and was used in three trials in 2021: parking bays at the University of Manchester; a mezzanine deck at the Mayfield Depot, a cultural venue in Manchester; and for the floor slab of a gym in Amesbury, Wiltshire.

Having shown a 30% improvement in compressive strength in the laboratory, real-life trials – using graphene from a variety of sources – achieved an average of 18% uplift in strength, the highest being 22%, says Beck. “The biggest challenge we faced after the 2021 trials was variability of performance in batches of one of the graphene materials we had sourced from overseas.”

“It is not only strength that is important. How will this be performing and how will it have degraded in 120 years?”

To create its Gen 2 additive, Concretene worked with two UK chemical companies, Thomas Swan – which owns Black Swan Graphene – and William Blythe, to redevelop the formulation. The first field trials for Gen 2 Concretene took place in December 2024. “The results are still pending, although indicatively they look comparable to the best-performing from Gen 1,” says Beck.

Spanish company Graphenano Smart Materials seems to be further ahead than its UK counterparts. It launched its graphene-based additive six years ago and has sold over 1,000 tonnes to date, according to its president Martin Martinez Rovira, a quantity it forecasts to multiply by five in 2025 alone.

“Our new version of the concrete additive, version 2, will soon be launched on the market,” says Rovira. “This version significantly improves upon its predecessor.”

Back in 2022, Graphenano started supplying its additive to ready-mix supplier Beton Catalan, part of the CRH Group, and is working with various overseas partners on projects that include a lightweight, low-strength concrete and a mix that uses desert sand. Graphenano is also developing graphene-reinforced fibreglass rebar, which Rovira says will be a game-changer when combined with graphene-enhanced concrete.

Precast first

Although graphene could in theory be used in any concrete application, the biggest immediate potential seems to be for precast elements. Precast concrete manufacturers have typically used 100% Portland cement, with high proportions of binder to give them rapid strength gain.

“Properties such as improved early age strength could be very significant for precast manufactures,” says WSP technical director and concrete expert Jimmy Barratt-Thorne. “A faster cycle time means quicker production.” Precast product manufacturers also have tighter quality control over the concrete they use, he adds, and could afford to assure their graphene-enhanced products through testing.

As well as its live field trials on slabs, Concretene is working on two projects with precast companies, with trials on precast concrete piles in January and February 2025 at Roger Bullivant’s Swadlincote HQ, and work with the Global Centre for Rail Excellence and Cemex to investigate its use in railway sleepers.

Ireland’s Banagher Precast Concrete carried out trials with Versarien’s graphene-based additive Cementene in 2023. According to Versarien, these demonstrated that the same performance could be achieved with 20% less Portland cement.

Catalan precast concrete manufacturer Hormipresa began working with Graphenano’s additive in April 2022, after trials showed its use reduced carbon emissions and water use by 20%. Other benefits of using the ‘Grapheconcrete’, says Hormipresa, is that the concrete is more compact with better impermeability and hence durability.

Graphene-enhanced additives

With fewer and fewer concrete mixes containing only Portland cement, the next step is to create graphene-enhanced additives that work with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) such as ground granulated blastfurnace slag (GGBS) and pulverised fuel ash (PFA). This is more challenging, says Hodge: “Graphene is straightforward with a CEM I mix but once you start using GGBS, some of the results are a bit hit and miss. You have to understand what’s going on; there’s quite a lot of work to do.”

Graphenano’s additive has already been used with SCMs, says Rovira, and even volcanic ash. In the UK, Breedon laid a test slab in 2023 using a graphene-enhanced CEM II/A-L (Portland limestone cement) mix.

Concretene too is working with mixes containing SCMs, says Beck. “Our pour before Christmas used a Breedon CEM III mix design with GGBS and Roger Bullivant’s mix is also CEM III GGBS. With Cemex, we’re working on a CEM II limestone mix design,” says Beck. “One of the main differences in our Gen 2 development has been the use of more industry-relevant mixes, as opposed to CEM I, which is now less commonly used.”

Cemex is leading a project, with partners Galliford Try, Sika, Northumbrian Water and Graphene@Manchester – part of the Graphene Engineering Innovation Centre – to produce an SCM that combines micronized limestone and graphene, with the help of Innovate UK funding.

Long-term performance

For graphene to take the step into everyday use, the industry and investors need cold, hard facts in place of hyperbole, says Beck.

“One barrier is about perception of nanomaterials and the idea that graphene is ‘magic dust’ that you sprinkle into a concrete mixer and somehow transforms the performance of your concrete. ” he says. “Even if people have heard of graphene, they often don’t understand how much chemistry and engineering goes into benefiting from its properties.”

One of the key questions for designers is how graphene-enhanced concrete will perform in the long-term, says Barratt-Thorne.

“It is not only strength that is the most important aspect. Durability comes into play, particularly in an external environment. How will this be performing and how will it have degraded in 120 years? How does it react with reinforcement, prestressing? This is a complex nano material and there’s a lot going on.”

For now, Concretene is focusing on collecting robust data, says Beck, working with its equity partner Arup. As for the future, it seems certain that graphene-enhanced concrete will have a role to play – although predicting just how is difficult to say.

“This is still just the start of developing a commoditised industrial process that may look very different in 10 or 20 years’ time,” says Beck. “One metric of success for graphene is that we’ll have stopped talking about graphene. In the same way that carbon-fibre and silicon were once novel but eventually became commodity products, the same applies to graphene. It will simply be one component among others in better-performing products.”