The uncertain outlook for the year ahead is fuelling construction’s confidence crisis, writes Nitesh Patel

For construction, 2025 was expected to be a big year and it has been pivotal for UK infrastructure, with government commitments setting the stage for transformative change.

Planning reforms and the government’s industrial, infrastructure and housing strategies are central to boosting growth.

In the November budget, while light on big-ticket announcements, the chancellor did reveal new funding for the Lower Thames Crossing, alongside the backing for nuclear at Sizewell and at Wylfa, and for the DLR extension to Thamesmead.

The 10 Year Infrastructure Strategy marked the UK’s first comprehensive long-term plan for infrastructure. It brings together economic infrastructure, such as transport, energy, water and wastewater, digital and flood risk management, with housing and social infrastructure, including hospitals, schools and colleges, and prisons and courts.

Over the next decade, the government has committed at least £725bn in funding. This certainty will enable both government and industry to plan further ahead, driving more effective project delivery.

To deliver on this vision, the Planning and Infrastructure Bill introduced in March aims to streamline the delivery of new homes and critical infrastructure across England. It also gives ministers the authority to prevent local councils from blocking new housing developments.

At its core, the bill sets an ambitious target: 1.5m new homes in England by 2029.

However, significant concerns remain about the industry’s capacity to meet the surge in demand. While materials price inflation has eased, rising wages growth and regulatory compliance continue to drive costs up, further squeezing margins.

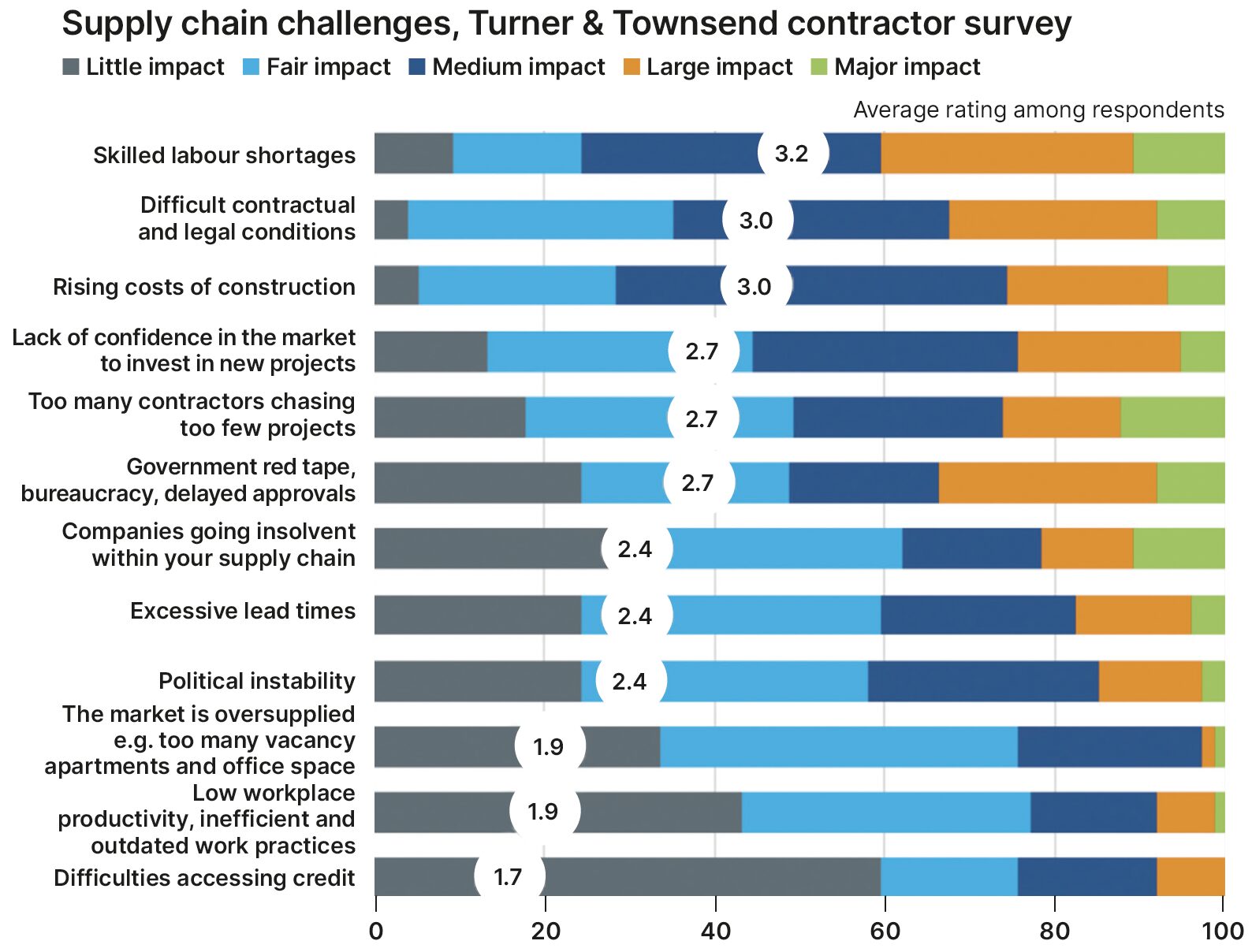

Labour shortages have been a persistent challenge in recent years, and our contractor survey highlights skilled labour as the single biggest barrier to delivery, ranking even above cost pressures.

Industry estimates indicate that the UK will need to recruit an additional 239,000 construction workers over the next five years to meet demand. In March 2025, the government pledged £600m to train up to 60,000 skilled workers by 2029. While this still leaves a shortfall, it represents a step in the right direction.

However, tighter visa rules for skilled workers raise the risk of further labour shortages and project delays, both of which inevitably drive up costs.

Adding to these pressures, the record number of construction insolvencies since 2021 has heightened supply chain vulnerabilities and created further uncertainty around project delivery. Greater clarity on funding should help stabilise the market and give contractors confidence to commit.

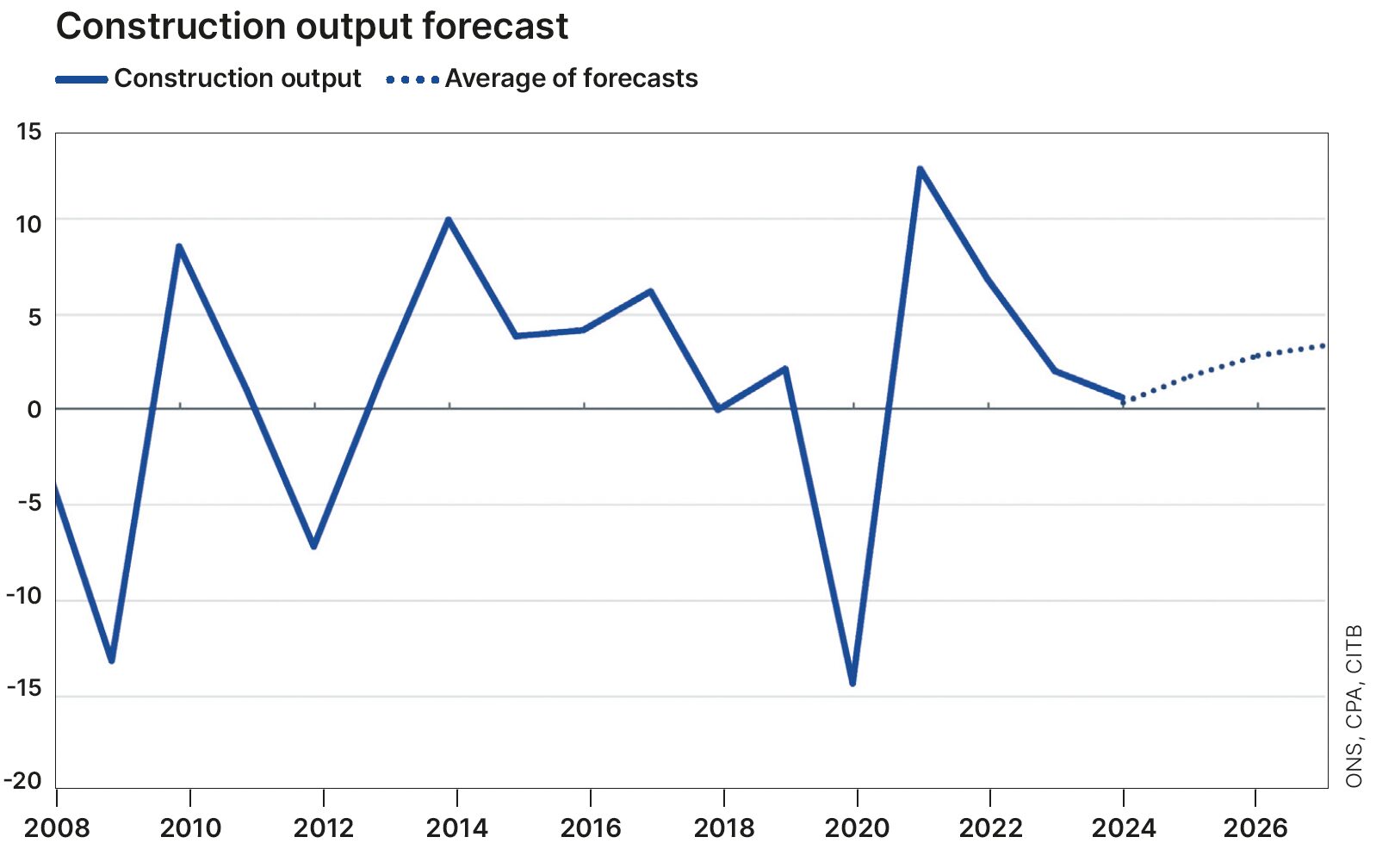

The wider economic environment also poses many challenges. Growth has slowed, and consumer price inflation picked up in 2025 due to higher utility costs, keeping interest rates elevated for longer.

Inflation is expected to ease in 2026, paving the way for bank rate cuts that should stimulate activity. Forecasts suggest output could grow by 2.8% in 2026, up from 1.5% so far in 2025. Combined with a loosening labour market, stabilising material prices, and government reforms, these factors should improve project viability over the medium term.

Construction is facing a confidence crisis. Conflicting signals from the government have made businesses hesitant, pausing investment and delaying projects that underpin economic growth.

Delivering Labour’s vision, of 1.5m homes and major infrastructure projects depends on a strong, confident construction sector.

The tax-raising measures announced in the budget must translate into tangible infrastructure investment. Without this, key projects risk competing for limited resources, driving up costs and constraining growth.

Nitesh Patel is a lead economist at Turner & Townsend.