Why heat pumps should be hot for commercial buildings

Few solutions are true silver bullets when it comes to decarbonisation, but for commercial buildings, heat pumps could hit the bullseye by halving energy consumption. Mott MacDonald’s Chris Vallis explains.

Homeowners who have had heat pump systems fitted are usually evangelical about them and readily share in-depth technological knowledge about finding the sweet spot for setting them up. Applying the technology on a commercial scale can also bring huge benefits for both building owners and the environment.

Although heat pumps are being specified more frequently in non-residential properties, finding the sweet spot for a large building calls for more detailed upfront planning than for a residential setting. Larger buildings also have greater energy demands and often ageing infrastructure, which add to the challenges.

Register for free or sign in to continue reading

This is not a paywall. Registration allows us to enhance your experience across Construction Management and ensure we deliver you quality editorial content.

Registering also means you can manage your own CPDs, comments, newsletter sign-ups and privacy settings.

Retrofitting heat pump systems into existing commercial buildings requires detailed assessment of the current energy performance, fabric and heating and cooling systems. Plus, any new system must be integrated with other sustainable technologies to ensure an effective decarbonisation strategy.

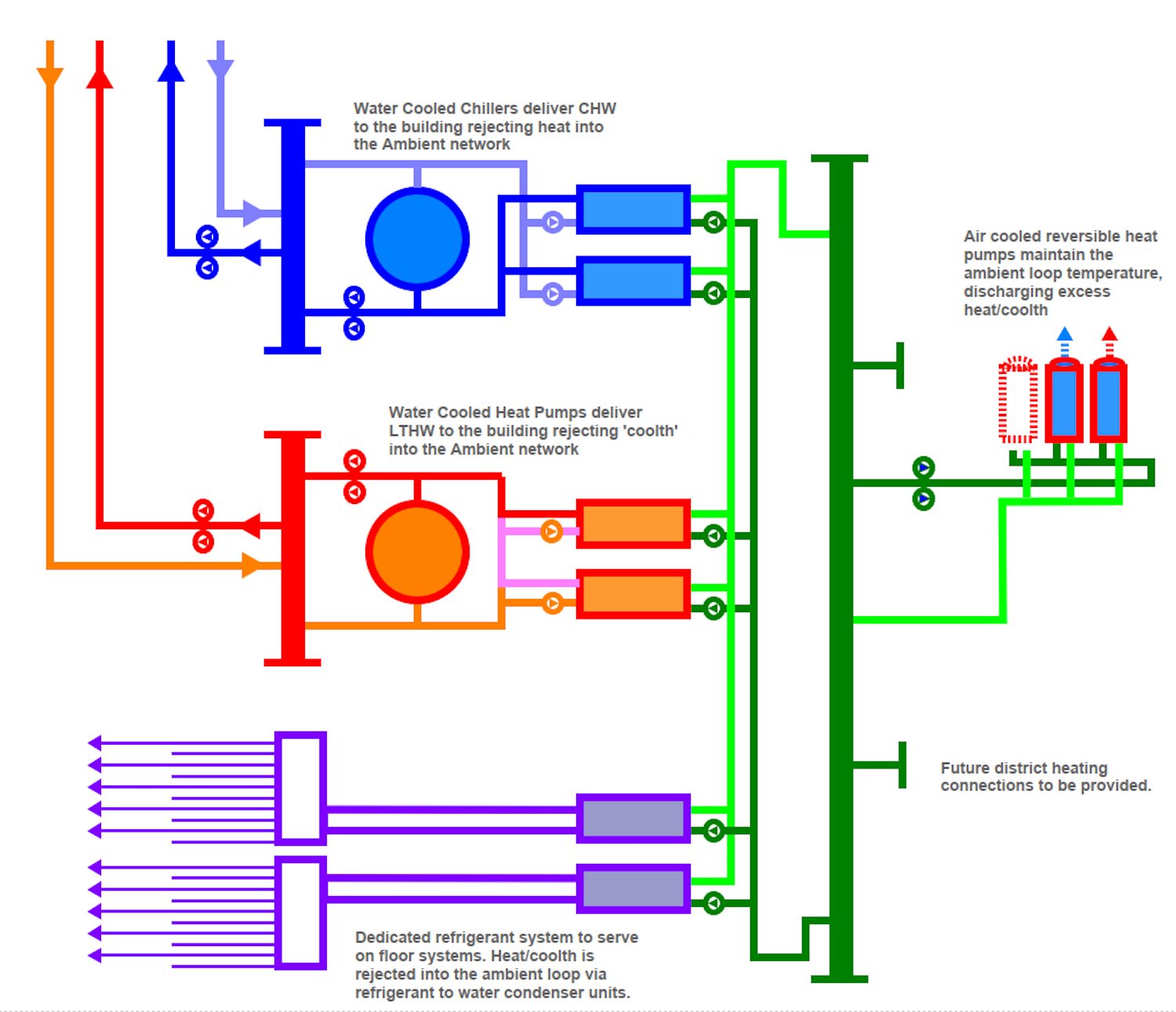

Large commercial buildings typically rely on more centralised heating systems, making large central air source heat pumps (ASHPs) or ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) a better option than smaller, distributed individual units.

Heat transfer

Understanding how the technology works is an essential starting point to ensure the system delivers the desired performance.

Heat pumps work by transferring heat from one location to another, using electricity to power the process. ASHPs extract heat from the outside air, while GSHPs absorb heat from the ground. In commercial settings, GSHPs are often more efficient, but require significant space for installation, which limits their use to larger estates.

ASHPs, while easier to install and generally more versatile, tend to lose efficiency in colder climates. Recent innovations have reduced the need for hybrid systems that rely on fossil fuel backup in colder climates. Newer cold climate ASHPs can operate efficiently at outdoor temperatures as low as -25°C and sometimes even lower.

For areas where extreme cold still necessitates a hybrid system, non-fossil fuel backup options, including electric resistance heaters, thermal storage, biomass systems, renewable-powered hydronic, and district heating systems, offer pathways toward full decarbonisation.

Commercial heat pumps can deliver significant energy savings. According to data from real-world projects, well-designed heat pump systems can reduce energy consumption for heating, especially when integration into building management systems has been carefully planned. These savings can be even greater when combined with energy storage and renewable power sources like solar panels, a stepping stone to realising 24/7 carbon-free energy and eradicating indirect Scope 2 emissions.

Putting heat pumps into practice

To explore the potential of heat pumps in commercial projects, let’s consider a large office building aiming to reduce its energy consumption and carbon footprint.

Office buildings, particularly those with open-plan designs and central HVAC systems, have high heating and cooling demands throughout the year, as well as varying daily and weekly occupancy levels.

The starting point for selecting the right system for each project is a detailed building performance review, which includes metered energy consumption data, occupancy patterns and details of the building fabric and services.

By using smart sensors and a digital energy twin to model potential operating modes, it is possible to accurately assess the building’s energy use. This can be split into peak and off-peak hours via real-time data on occupancy and environmental conditions to identify inefficiencies in the total energy system, as well as allowing for whole system optimisation.

Armed with this knowledge, along with an assessment of the building’s heating and cooling systems, the feasibility of implementing a heat pump strategy can then be explored. Given the urban setting of most office buildings, an ASHP is likely to be the optimal choice due to space constraints, plus it can be integrated with the existing HVAC system to deliver consistent heating and cooling.

Dynamically adjusting temperatures

The system will reduce energy consumption by optimising heating and cooling when the building has low occupancy, such as overnight or during weekends via integration with smart controls. This type of system can dynamically adjust temperatures, based on real-time occupancy data, to automatically reduce heating during off-peak hours and minimise unnecessary energy consumption and maximise efficiency.

This approach, combined with the latest ASHP technology and a well-insulated building envelope, could result in energy savings of up to 50%, although the actual cost savings can vary based on building insulation, climate and system design. The actual savings will also vary according to the current spark ratio – the difference in prices between gas and electricity. The switch to electrified heat also reduces the building’s Scope 1 emissions by removing fossil fuel use on site.

The savings seen on projects delivered by Mott MacDonald are backed up by data from the Carbon Trust, which shows that well-designed heat pumps in commercial settings reduce energy consumption by between 30% and 50%.

Challenges and complications

Getting the right set-up for each individual building is not the only consideration around heat pumps though – there are other environmental issues and hurdles that need to be addressed.

One key complexity of heat pump systems is the refrigerant used, which can affect both performance and environmental impact. Many heat pumps rely on hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants, which have a high global warming potential (GWP) if leaked. Newer systems use hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) with a lower GWP, but these are now recognised as part of the PFAS – forever chemicals – group, which can pose long-term environmental risks.

Natural refrigerants, such as CO2 and propane, provide the most sustainable alternative, as they have minimal environmental impacts and zero ozone depletion potential. When considering heat pump strategies for large commercial buildings, selecting a system with the right refrigerant is crucial for minimising Scope 1 emissions and aligning with future environmental regulations.

High upfront costs

The main barrier to wider adoption are the high upfront costs and the skills gap in the industry with few consultants and contractors currently having the knowledge and experience of designing, installing and maintaining these systems for largescale commercial projects.

However, as energy prices fluctuate and regulatory pressures mount, heat pumps are becoming increasingly attractive on cost grounds and this growth will drive up expertise. Government incentives, such as grants for renewable energy projects and carbon reduction schemes, are helping to offset installation costs, making it easier for businesses to justify the initial investment.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to heat pumps, but when combined with smart building technologies, renewable energy sources and efficient design, there are significant cost and carbon savings to be made. While challenges remain in scaling up this technology for commercial use, the benefits are undeniable, and heat pumps are likely to play a central role in the transition to a more sustainable future.

Chris Vallis is director of sustainable buildings at Mott MacDonald.