This year, ground engineering specialist Treviicos expects to finish a decade-long project to shore up the 230km Herbert Hoover Dike in southern Florida. Rod Sweet reports.

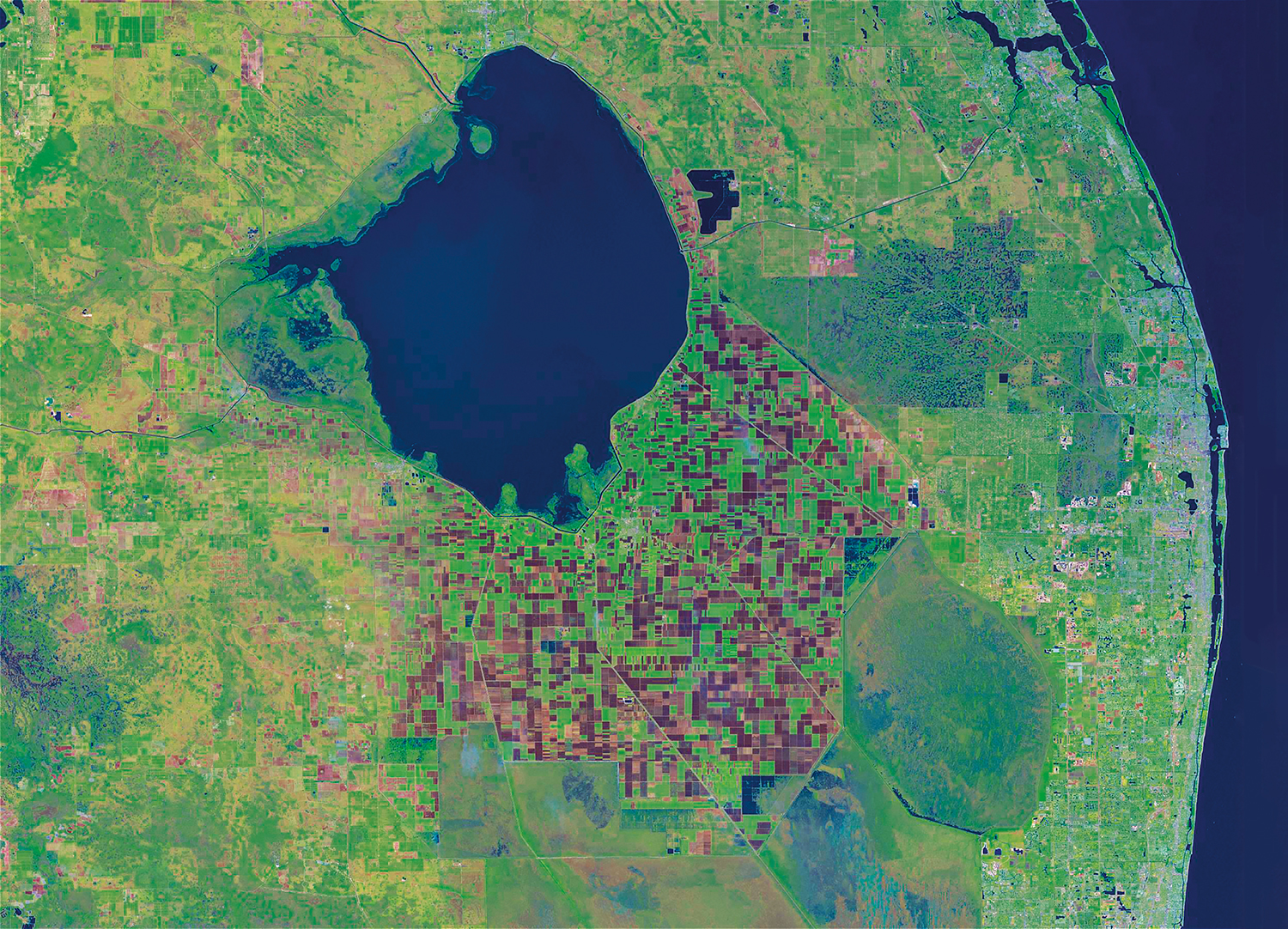

Life around Florida’s biggest lake, Lake Okeechobee, has always been risky. Water levels rise during the rainy season from May to October. And when farmers began cultivating the rich soils around it in the 1910s, they knew enough to construct rudimentary embankments around its perimeter with sand and mud.

That was fine until 1926, when the Great Miami Hurricane struck, killing some 300 people. Two years later in 1928, the Okeechobee Hurricane caused a catastrophic breach, with floodwaters killing nearly 3,000 people, most of them non-white migrant farm workers.

The River and Harbor Act of 1930 authorised the construction of some 110km of levee along the south shore of the lake and 25km along the north shore. The US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) constructed the levees between 1932 and 1938.

Another major hurricane in 1947 prompted a comprehensive overhaul of the dike system, finishing in the late 1960s, when it was named the Herbert Hoover Dike, in honour of President Hoover’s visit after the 1928 disaster. But constant seepage of water through the earthworks continued to threaten

its structural integrity.

By 2001, some five million people lived in the counties to the south east of the lake. That year, USACE embarked on the latest programme of shoring up the vulnerable structure with a combined cost of $870m (£744m).

Dam within a dam

Without USACE’s interventions, which include the ongoing management of the lake’s volume, surrounding towns could have been wiped out in the many hurricanes since the 1960s. But USACE continues to view the delicate balance of water and earth as a dynamic risk.

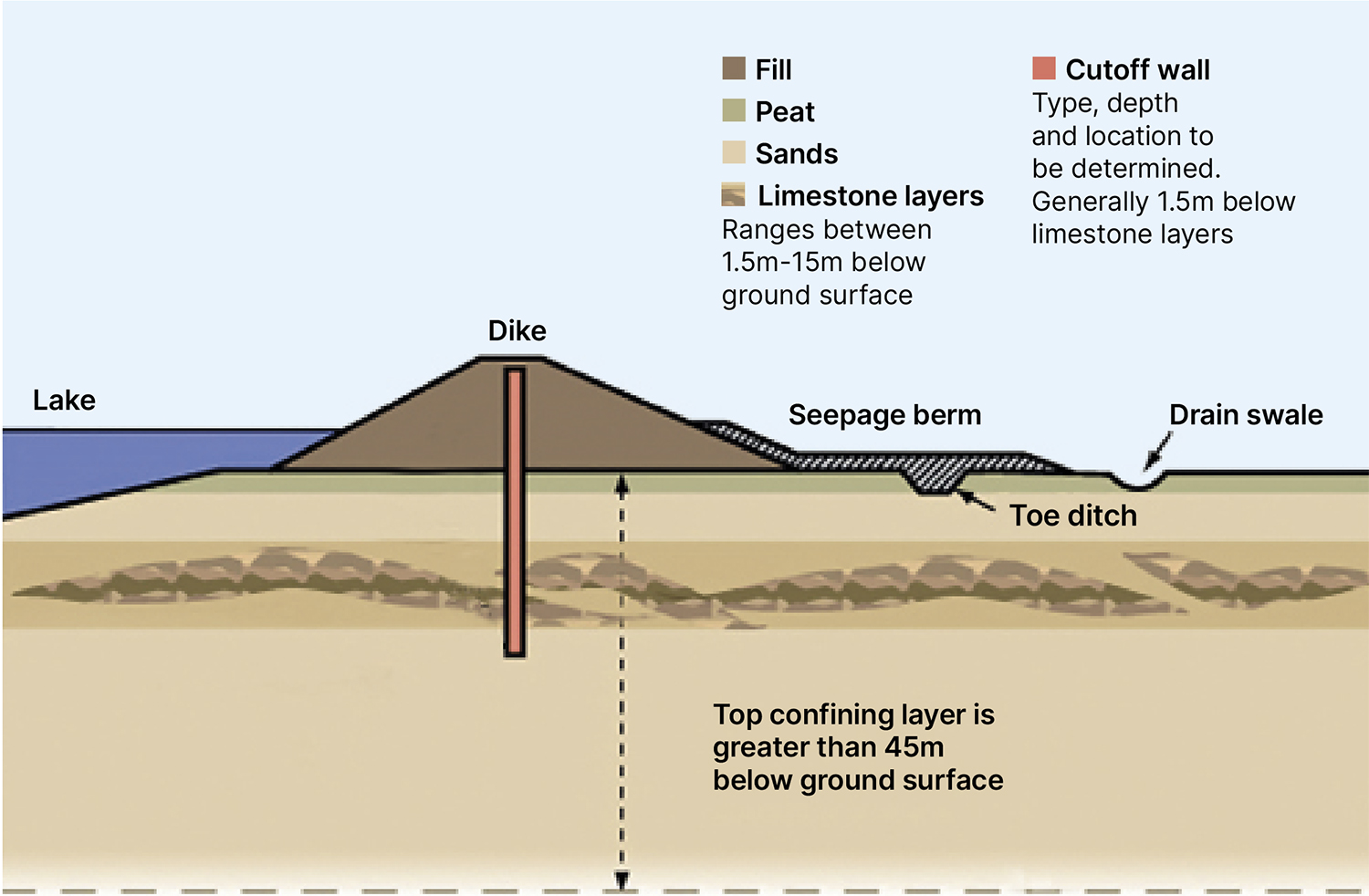

The centrepiece of its latest effort has been the insertion of a low-permeability cutoff wall within the dike, made of self-hardening slurry, a technique pioneered by ground engineering specialist Treviicos, the North American subsidiary of Italy’s Trevi Group.

In two phases – 2008-12 and 2016-22 – Treviicos inserted 40km of cutoff wall along sections of the dike deemed most at risk, Treviicos project managers Carlos Morales, Pablo Bassola and Filippo Maria Leoni told CM.

“The slurry is an engineered mix of Portland and slag cements, bentonite, additives and water, which acted both as excavation support and permanent backfill,” they explained.

“The cutoff wall is not a rigid element, but it limits water flow while integrating structurally with the earthen levee.”

By the end of this year, Treviicos will have inserted 670,000 sq m of the slurry to create a dam-within-a-dam. In height, the wall extends from the top of the existing dike down to a depth of 26m. Treviicos used a mechanical clamshell to dig out soft soil and a crane-mounted hydromill to excavate harder limestone layers.

It used jet grouting to seal areas abutting existing concrete structures such as gates and locks. Trevi Group says it was the longest and most challenging project in its North American history.