Justin Stanton, editor of CM‘s sister title BIMplus, reviews the technologies that have disrupted the construction industry this year.

Setting-out robots

If you attended the UK Construction Week or Digital Construction Week exhibitions in the spring, you would have struggled to avoid the UK launch of HP’s SitePrint robot.

It prints lines and complex objects accurately and with consistent repeatability on site floors, says HP. It can also print text and thus bring additional data from the digital model to the construction site. In addition, it is autonomous and can avoid obstacles.

Both John Sisk and the Vinci Building/Sir Robert McAlpine JV, Integrated Health Projects, successfully tested it.

Meanwhile, Ferrovial not only tested SitePrint, but also the outdoor setting-out robot from Civ Robotics.

Body cameras

While body cameras are not a new thing in law enforcement and are gradually becoming de rigueur for workers in public-facing roles, they’re not a part of the established construction toolbox.

Thus, Axa UK’s move to provide body cameras to contractors to keep a record of remediation work being carried out on buildings that contain flammable cladding and insulation makes this list.

The recordings from the body cameras will provide detailed information about materials used, together with evidence of working practices and site management for the areas being refurbished.

Sound modelling

There’s not a lot you can’t do with 3D modelling, but how do you realistically predict sound and acoustics? Step forward Treble Technologies, a start-up in Iceland, and its Treble platform that enables engineers, designers, architects and developers to design and virtually prototype sound experiences.

Treble claims this is the world’s first sound simulation platform, allowing stakeholders to not just see how their designs will look, but to simultaneously hear exactly how they will sound in real life.

Hard science to the rescue

Microgravity technology. Cosmic radiation monitoring. Gravity gradiometry. 2023 saw hard science offering solutions to major infrastructure issues.

The Defence and Security Accelerator highlighted the work of Cambridge University spin-out Silicon Microgravity. The latter is developing a gravimeter, a tool for measuring minute changes in the force of gravity, which can be deployed remotely on an autonomous land vehicle or drones, to detect underground structures, keeping workers out of danger zones.

The Defence and Security Accelerator, along with the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority, also highlighted Glasgow-based Lynkeos Technology’s use of muography. This is a technique that uses natural radiation (cosmic ray particles) to monitor complex structures and assess their integrity, including identifying any voids or any degradation of steel reinforcement bars. This project seeks to develop a portable muography capability for monitoring underground, ageing reinforced concrete infrastructure.

Finally, University of Birmingham spin-out, Delta g, is pioneering the use of gravity gradiometry for underground mapping. Gravity gradiometry can measure subtle changes in the pulling strength of gravitational fields when clouds of atoms are dropped.

AI assistants

In 1989, Kate Bush detailed a human being’s relationship with their computer. In the 2010s, Apple deployed Siri, Amazon unleashed Alexa, and Joaquin Phoenix fell in love with a Scarlett Johansson-voiced AI assistant in the movie, Her.

Now, virtual assistants are set to be your new, potentially very helpful colleague. This year we reported on two in particular.

First, Wendy, developed by Aiforsite, can respond in real-time to text or voice on a smartphone, tablet or computer. Wendy can manipulate a BIM model, get product information from the model, generate 2D images from it and link other data sources to it, according to Aiforsite.

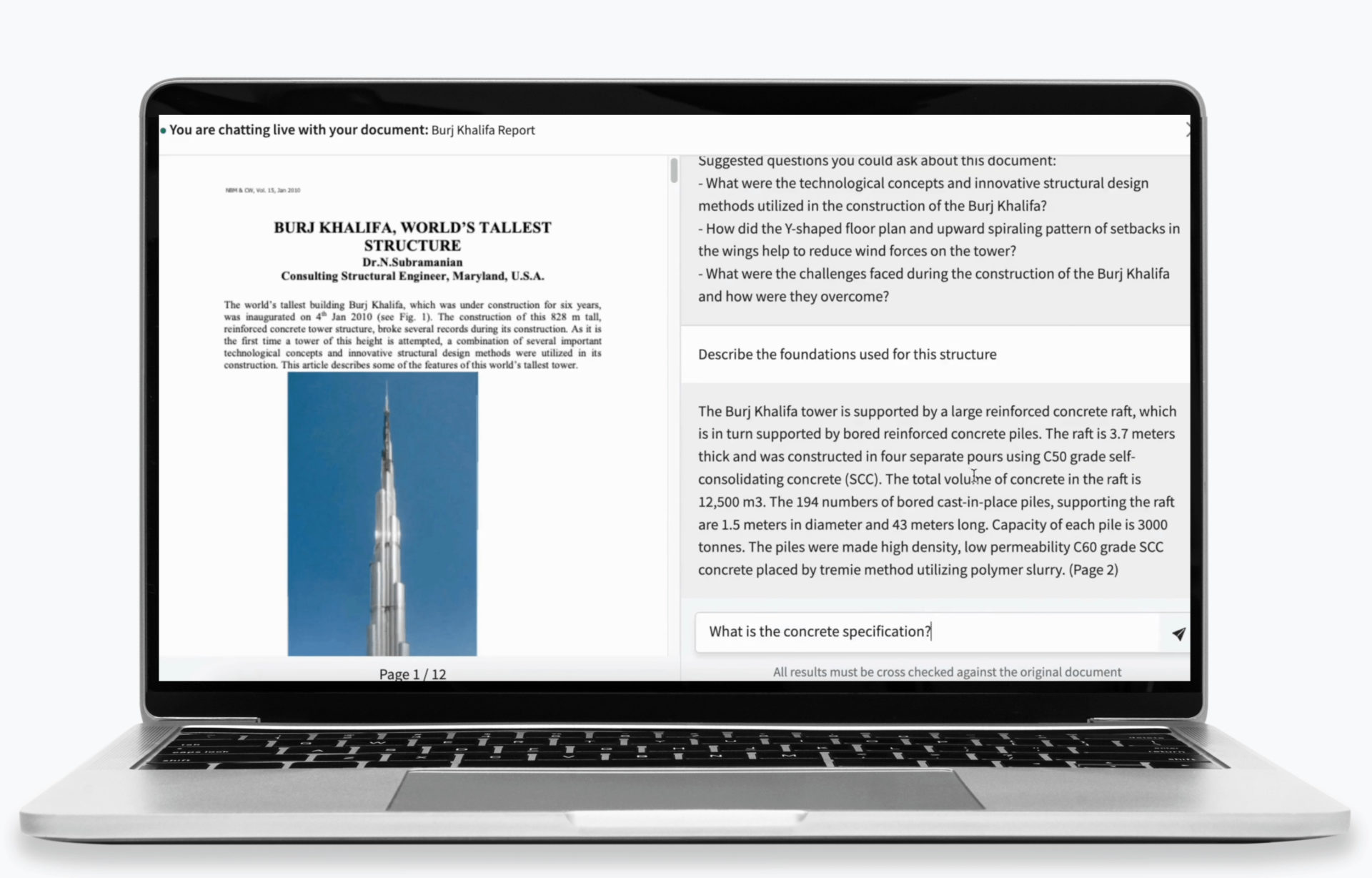

Then came a construction chatbot developed by former Arup engineer Stefan Lukic. He has led a team to develop Civils.ai: a tool that uses a large language model (LLM) to generate answers tailored to construction projects.

Users upload datasets, such as site reports, contracts or design codes, that the AI processes to generate answers to specific questions posed by users relating to their project.