The built environment could play a significant role in rebalancing the economy across UK regions – but there are challenges ahead for policymakers and industry. Economist Brian Green speaks to Will Mann about his new CIOB-commissioned report.

“Construction faces its biggest challenge since World War Two,” says Brian Green. The industry economist and author of The Real Face of Construction, first published in April 2020 and now updated for 2023, pulls no punches in an interview with CM.

“The three Ds of demographic change, digitalisation and decarbonisation will have a fundamental impact on society and the economy,” he says. “UK politicians and industry leaders will need to look hard at how best construction can play its role. This means looking not just at the national viewpoint but the regional picture too.

“The longstanding debate over how to rebalance the UK economy has lingered for more than a century. Once described as the north-south divide, it is now captured in the phrase ‘levelling up’.”

Green’s 2020 report, commissioned by CIOB, examined the regional imbalances in the UK economy and the construction industry and suggested measures for how to counter them, such as different regions becoming specialists in particular sectors.

“Insight on how construction is faring in the regions is critical to informed debates ahead,” says Green. “Local knowledge and understanding will be crucial if the construction sector is to rise to the challenges of climate change, an ageing population, technological disruption to the social and economic fabric, and the fairer spread of wealth and opportunity across the UK.

“Given the current turmoil, it could be even more important to have regional specialisms for construction – and join it with the levelling up agenda.”

Local level operation

As Green notes, construction operates from a local level, with small builders and trades who work mainly in their communities, though to the national level, with major businesses delivering megaprojects like Hinkley Point nuclear power station in Somerset or the HS2 railway which will cut across many regions.

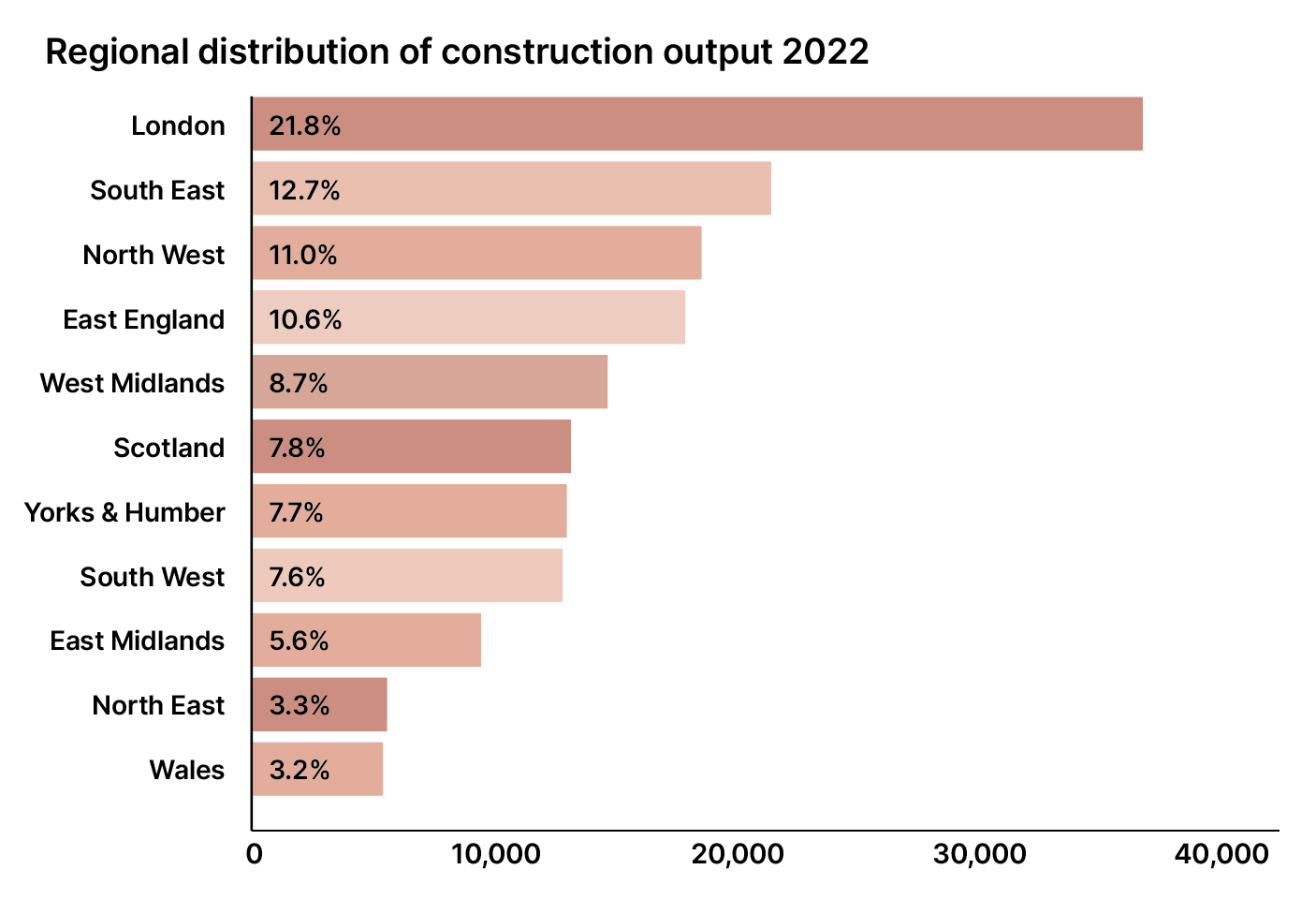

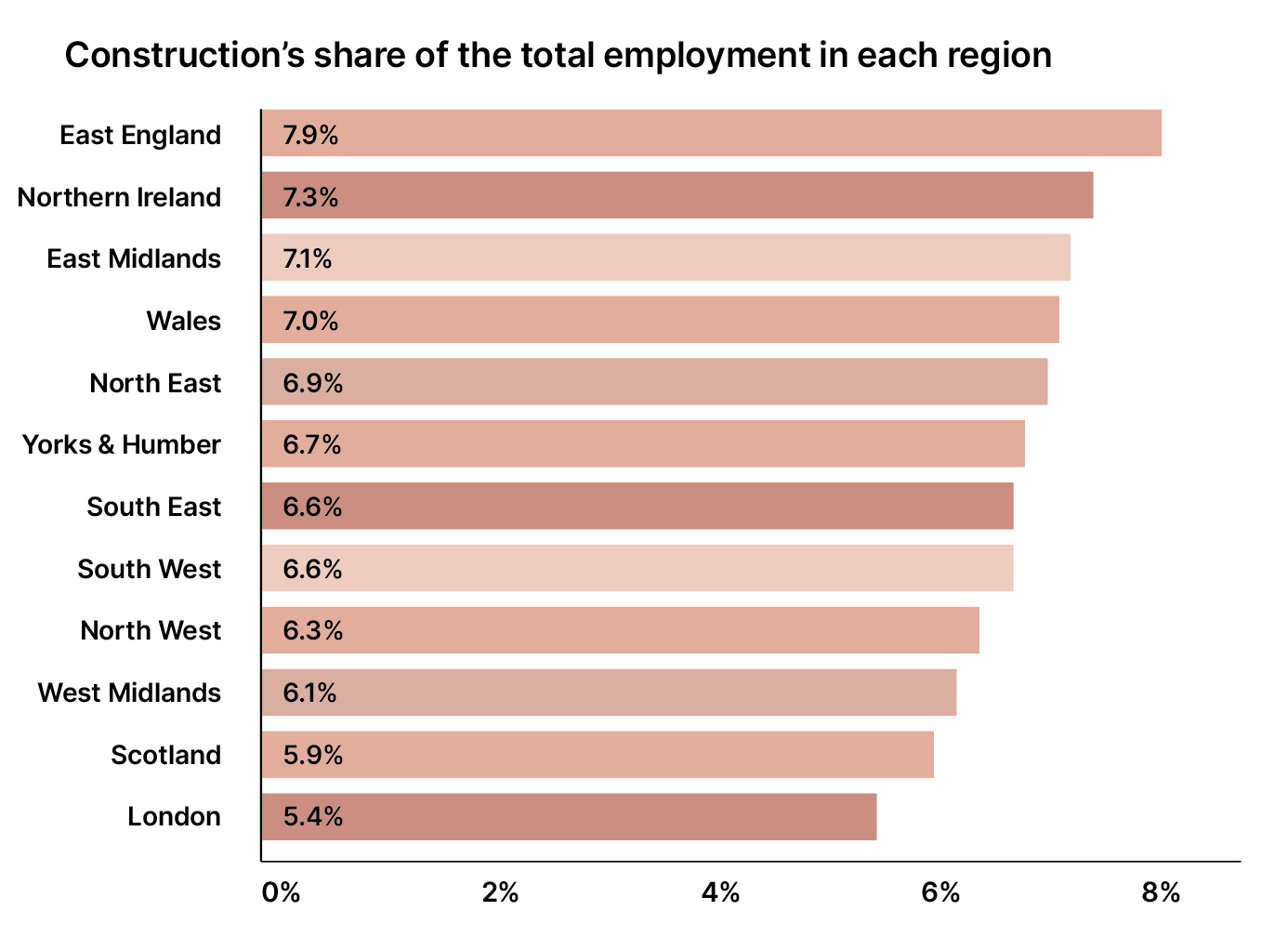

London dominates construction output among UK regions (see chart above). However, it is bottom when construction’s percentage share of total employment is measured (see chart below).

“This is because construction differs from most industries in that its firms and the workforce move to where the product is needed, rather than being sited in a fixed place,” Green explains. “Work in one region can benefit another, particularly in terms of employment.”

The East of England has the highest proportion of its workforce engaged in the construction sector. At 7.9% in 2022, this compares with 5.4% in neighbouring London. But a large cohort of workers from the East will travel to work on projects in London.

Construction and land value

“The nature of investment in the built environment means that the mix of activity, scale and fortunes of construction vary from region to region, and over time,” Green says. “But it is important to note that there are long-term differences in activity between regions.”

This is a frequent point in the levelling up debate and has been a regular complaint about the north-south divide, Green adds.

“Look closely and we can recognise at least two factors that create regional imbalances in construction activity and impact on the long-term levels of activity: land values and population growth. The link with population is easy to appreciate. With more people or faster population growth there will inevitably be higher demand, all other things equal.

“There is a clash between two policies – levelling up and decarbonisation – in a way it appears that policymakers haven’t really considered as carefully as they might.”

“The link between construction activity and land values is less clear. But if we were to plot on a graph average land value against the level of construction activity per capita for each region we would see a very clear correlation between higher land values and higher levels of construction. London, where land prices are extremely high, stands out.”

He continues: “The more investment a location receives, particularly in infrastructure, the more attractive it becomes, both to incomers and future investors.

The land value inevitably increases as does the population. This virtuous circle is increasingly well recognised and present in the current debate on levelling up.”

Stranded assets

In the context of decarbonisation, among Green’s concerns is a surge in ‘stranded assets’ – property or buildings in areas of low land value where the cost of meeting energy requirements makes investment to meet minimum energy efficiency requirements, repurpose the building, or redevelop the site unattractive to investors. This could result in poorer areas losing valuable buildings, such as offices or shops, essential for the prosperity of the local economy.

“This is a clash between two policies – levelling up and decarbonisation – in a way it appears that policymakers haven’t really considered as carefully as they might,” says Green.

The problem of stranded assets could be further exacerbated by the high inflation currently affected the construction sector.

“The impact of higher labour and materials cost will have a disproportionate impact on locations with low land values,” says Green. “This means, in general, that regionally inflation will hit the devolved nations and the North East hardest. The reason is that, by and large, materials and labour represent a larger share of the development cost where land values and property prices are low.”

Forecast for next five years

So, what can we expect regional output in construction to look like over the next five years?

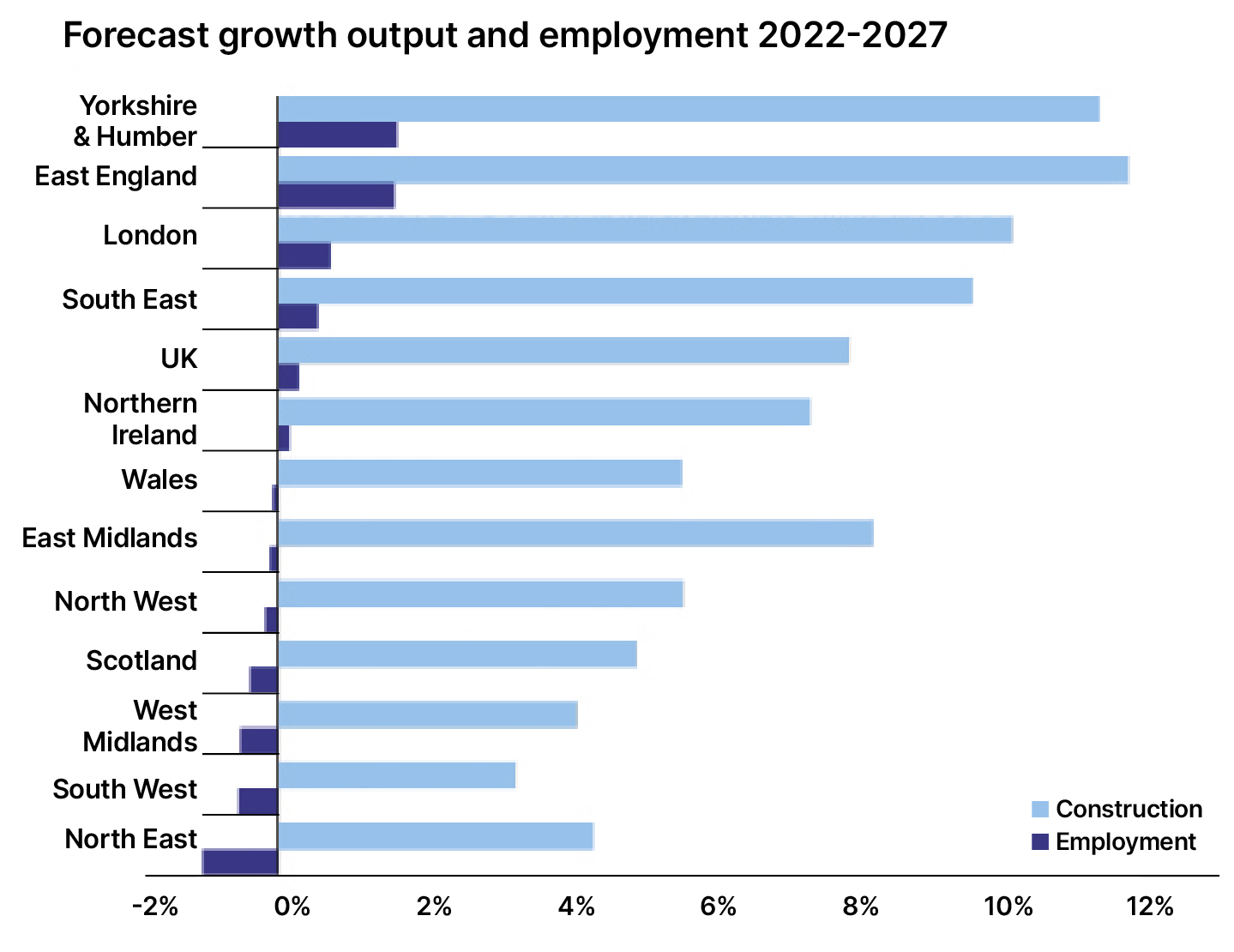

The forecast underpinning the CITB’s Construction Skills Network (CSN) employment expectations provides a starting point. The chart below outlines the forecasts for construction output and the change in the level of employment needed to deliver that workload.

“It’s worth noting that other forecasts, such as from the Construction Products Association (CPA) in January 2023, paint a darker picture of the future for construction than the CSN forecast, notably in new housebuilding, where CSN sees a minor dip while CPA sees a fall of 11% in its main forecast,” Green says.

Population growth is a long-term driver of construction activity. East Midlands, the South West, and West Midlands represent about a quarter of the national population, but the prediction is they will absorb about 40% of population growth over the next 20 years, which points to a growing share of construction activity.

Increasing need for construction

Green believes the underlying need for construction is increasing. He also argues that the need to transform the built environment is “greater than it has been for a generation or two”.

“The need to accommodate an older population, the need to decarbonise the economy and the need to reconfigure the building stock to address massive changes in working and shopping habits are all very pressing,” he says.

This will require smart policies and smart thinking from the industry, Green reasons.

“There is a massive amount of decarbonisation work ahead, which construction is just starting to get to grips with,” he says. “For example, Willmott Dixon has launched its ‘Decarbonise Today’ service, which aims to help customers understand and upgrade their buildings to meet net zero and decarbonisation requirements.

“There is also work in converting offices and retail, but this will be a challenge in areas of low rental value – the government needs to recognise this.”