Nearly 200 construction workers a year suffer from head injuries in Great Britain. CM, with MIPS, which focuses on reducing the risk of head injuries, asked a panel of health and safety experts how the industry could address the issue, and whether new helmet technology could help

Roundtable participants:

- Steve Coppin: Technical director, Arcadis; CIOB health and safety special interest group

- George Mosey: Head of health, safety and environment, Europe, Laing O’Rourke

- Mark Starling Safety, health and environmental manager, Kier Construction; CIOB health and safety special interest group

- Derek Rees Programme director, Construction Logistics and Community Safety; chief executive, SECBE

- Andrew Hughes: Global health and safety director, ISG

- John Dunne: Group health, safety, environment and quality director, Wates

- Will Mann (chair): Editor, Construction Manager

- Max Strandwitz: CEO, MIPS

- Peter Halldin: Chief science officer, MIPS

- Olof Rylander: Business developer safety, MIPS

Will Mann: Health & Safety Executive statistics from 2016/17 to 2018/19 show that 595 construction workers suffered head injuries. Of these, 186 resulted in loss of consciousness and 79 caused concussion. What are the panel’s views on how head injuries in construction could be prevented?

John Dunne: A head injury is among the worst-case scenarios on site, but thankfully I can’t recall the last serious head injury that occurred on a Wates site. That doesn’t mean that one couldn’t happen though. Our focus is around prevention of the fall in the first place and the prevention of materials or equipment falling. Saying that, there is always the possibility that something will fall, so the right selection of head protection is a really important subject.

In general, we use JSP EVOLite head protection as our standard employee issue, tested to EN 397. Wates has a national agreement in place with Arco, who have plenty of options for personal protective equipment (PPE), and we choose what we feel is the right choice for us.

In association with:

Many larger organisations within our supply chain are well informed and provide a good standard of PPE to their employees. However, for smaller contractors who may not have access to up-to-date information or cutting-edge technologies, there could be a concern. Therefore, it is up to all main contractors to ensure we pass on any new information that comes to light that may make our sites safer.

At present, we don’t insist on the type of head protection that the supply chain use, provided it conforms to current safety standards. We could insist that anyone working on our sites use a certain type of helmet, but this could have implications in terms of cost and availability.

Andrew Hughes: At ISG, we have a helmet that has a chin strap which is different to others, and we insist on that throughout the supply chain. It was difficult at first to get people to buy into that process but incidents that have occurred have backed that decision up.

Yes, the hierarchy of controls should prevent accidents from happening in the first place, but when the consequence is significant – as is the case with head injuries – then using the latest technology to help mitigate the impact is definitely a good thing to do.

George Mosey: We’ve taken a look at some of our safety data recently and two-thirds of our small number of head injuries are impact-related. Fifty per cent are attributed to falls from height and 20% are attributed to objects falling from height onto a person. Also 15% of head injuries include contact to the face and that asks a question around what is needed to protect their face as well as their head. What this reiterates is the importance of wearing a hard hat at all times.

At Laing O’Rourke, we are actually trying to move to a position on some worksites where bump caps are appropriate, because we have de-risked the project to such an extent. However, that is not always appropriate, particularly at the start of projects.

Tethering of tools is another big area of focus for us – hand tools being used on scaffold platforms or MEWPs. They are things that have the potential to be dropped because they are often in people’s hands and people’s hands are fallible. PPE is the last resort.

Chin straps are not mandated across our operations but that is something we may look to do in the future.

“We have got to follow the science. If we feel that mitigating rotational impact should be a key consideration, then we should ensure that it is part of all future safety helmet testing”

John Dunne, Wates

Mark Starling: We had a crush incident at Greenwich three years ago, which demonstrated the importance of safety helmet technology. The worker was in a MEWP, but luckily he was wearing a higher-impact-resistant helmet and he had his chin strap on. Without that I think we would have been talking about a different scenario.

Derek Rees: I have been in the industry 30-odd years and while some things have changed hugely, some things have not. The attitude when I first started was that hard hats were quite handy to carry stuff around in. Now everyone does wear them, but I am not sure how much the technology has really shifted. We should use nanotechnology or similar to highlight where and when a hard hat has been dropped and damaged making it unsafe.

WM: Studies have shown the human brain is six to seven times more sensitive to rotational than linear motion. Almost all head impacts generate rotational motion. What can construction do to mitigate this?

JD: We have got to follow the science. If we feel that mitigating rotational impact should be a key consideration with head protection, preventing more serious injuries, then we should ensure that it is part of all future safety helmet testing.

AH: These oblique angle impacts are particularly relevant to our industry, as experience has shown that falling objects, ranging in size from a bolt to a scaffold pole, remain a rare but critical risk. It would be useful to understand more about how those impacts vary.

“There are two trades where safety risk is quite high; scaffolding and steel frame erection. When visiting sites during these stages of projects I wear the higher-standard impact-resistant helmet”

Mark Starling, Kier Construction

GM: We could break down falling objects into a number of categories. If something quite sizeable comes off a building and lands on someone’s helmet, I suspect there is a load or a weight limit you get to where actually no helmet will help. It could be helpful to analyse the different types of falling objects and their respective weights, then ensure the materials that constitute safety helmets can mitigate the impacts.

Steve Coppin: We need education around the potential scenarios. Some workers are undertaking more high-risk activities than others. There are many different types of helmet, but do our supply chain realise what the difference is between them? It is important to know which helmets are right for different tasks and work activities.

MS: Would the MIPS helmet need to be used site wide? There are two trades where safety risk is quite high: scaffolding and steel frame erection. When visiting site during these stages of projects, I wear the higher-standard impact-resistant helmet. All scaffolders in our supply chain wear the higher-impact-resistant industrial helmet from Petzl or an equivalent standard. I wouldn’t have a problem turning round to the supply chain and justifying the need to make the change to a higher-specification helmet. But maybe there wouldn’t be the same need for finishing trades like decorating.

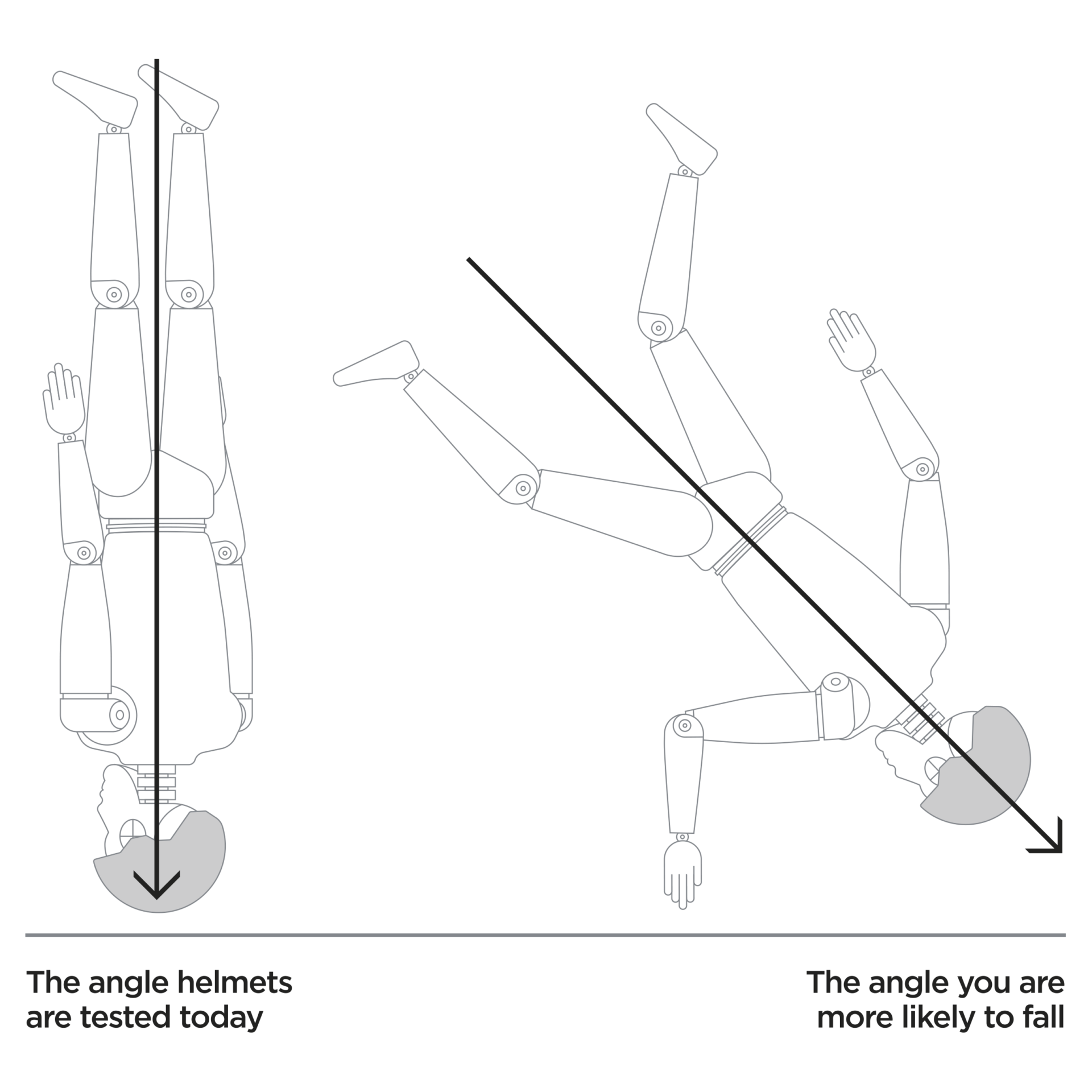

WM: The existing standard for testing safety helmets is EN 397 which dates back half a century and involves a 5kg weight being dropped 1m onto a helmet. What does the panel think of the existing standard and how fit for purpose it is?

SC: When we think about steel erectors and scaffolders, and the risks they are facing, I don’t think that standard is sufficient.

JD: I think 50 years is a long time for any standard to survive and a lot has changed in that time. Our priority needs to be preventing things from falling and preventing people from falling. I can see a day where you shouldn’t need head protection or any PPE on sites because we have all worked hard to make construction activity intrinsically safe. All of our sites are a lot safer now than they used to be, but we are not there yet so there is still a need for PPE and especially the best head protection.

AH: Everything has to evolve and standards need to evolve too. These new technological solutions should become part of the norm. But in any case, where we set the bar on safety shouldn’t just adhere to the standard, but be relevant to the level of risk.

GM: Half our head injuries are attributed to falls from height, and clearly the standard doesn’t account for that, so an upgrade is no doubt needed.

DR: When the standard was written 50 years ago, it was more focused on defining the physical integrity of the product, rather than the level of impact protection for the user. That needs to change.

MS: In 50 years, risk has changed. The most recent debate about helmets has been about the colour and not necessarily the impact resistance.

WM: What does the panel think of the potential of the MIPS technology to reduce head injuries?

AH: I can speak from practical experience. I like to mountain bike and so before I throw myself off a mountainside, I am thinking clearly about what sort of protection I am wearing. Having fallen off a few times, I did buy a MIPS helmet. I am convinced it is a level of protection above and beyond what currently exists.

What is MIPS technology?

Swedish company MIPS made its name through cycling safety helmets; now it is taking its helmet technology system to construction. CEO Max Strandwitz explains how the technology works

Developed by our team of 20 engineers, the MIPS technology is used by over 100 helmet brands in cycling, motor racing, horse riding and winter sports. We sold five million units in 2019. Now we are introducing our technology to construction.

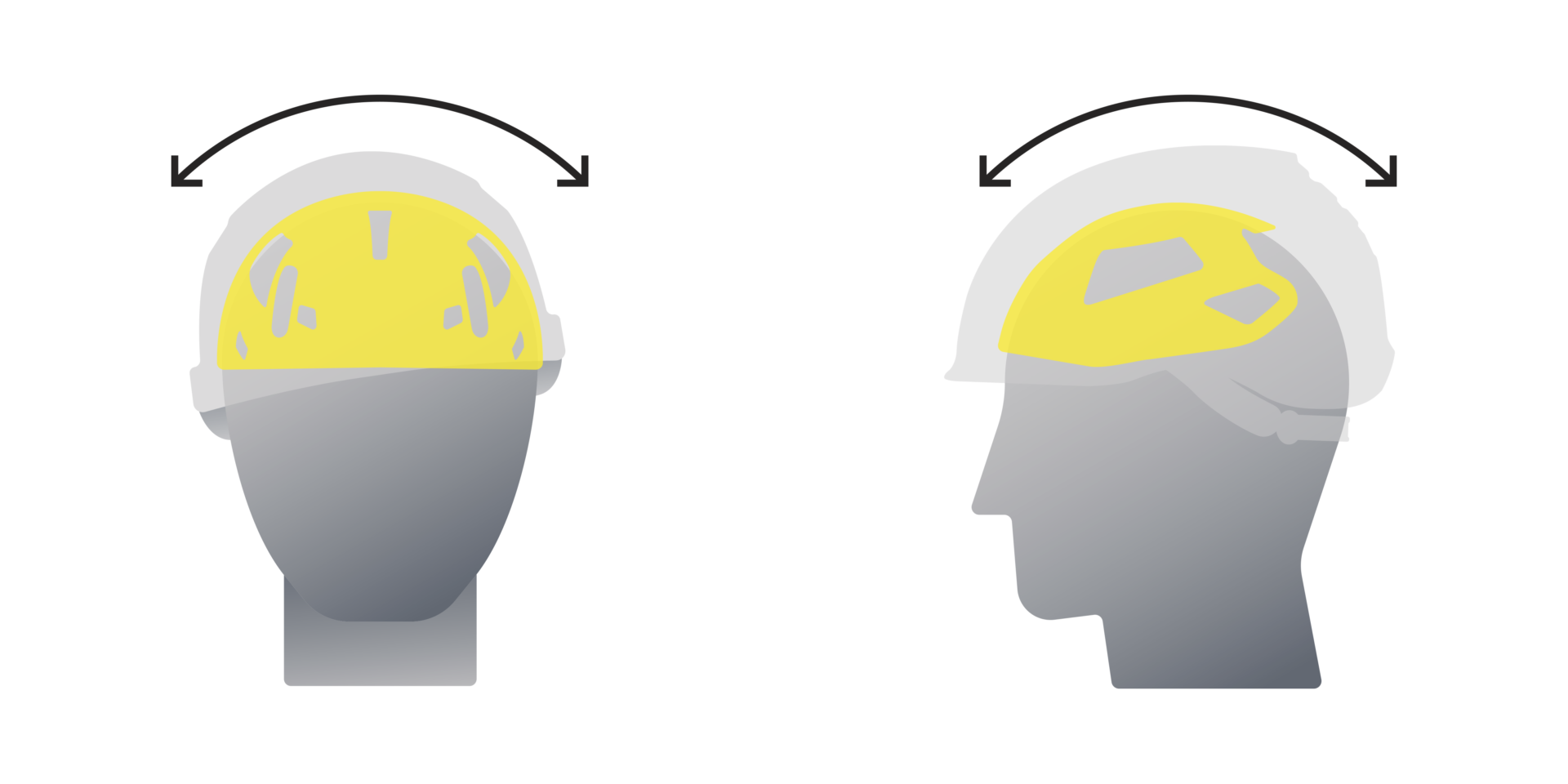

MIPS, which stands for multi-directional impact protection system, addresses rotational motion, which happens with most head impacts and which the brain is particularly vulnerable to. Compared to linear impacts, the brain is six to seven times more sensitive to rotational force.

The MIPS technology is designed to redirect energy otherwise absorbed by the head, through a low-friction layer inside helmets. MIPS is designed to reduce energies transmitted to the head by redirecting the dangerous rotational forces that are generated during the impact. It allows a 10mm to 15mm movement between the head and the helmet during the critical first five to 10 milliseconds of the impact.

In a construction scenario, if a worker falls or is struck by a steel beam on site, the MIPS-equipped helmet they are wearing allows the helmet to move independently from the head, so the head does not experience a sudden stop. With a sudden stop, the force needs to go somewhere and the force can be absorbed by the head – which can lead to brain trauma.

We have spent three years researching whether the MIPS technology can work in construction helmets, examining different types of accident leading to head injuries. EU data between 2014 and 2017 shows that severe impacts, which lead to fatalities, are over-represented in construction. Concussion is quite a common injury in the statistics and construction helmets’ standard testing today does not represent these accident types, leading to severe injuries.

We then used finite element (FE) models to simulate how the head behaves in different accident scenarios and how the MIPS technology would protect the head. The three most common accident scenarios in construction which cause head injuries are falling objects, being struck by a moving object, and falling from height. In trying to mimic real construction site accidents, we found that MIPS helmet redirected more energy away from the wearer’s head than a standard helmet.

SC: I see this helmet as a positive, but one of the questions here will be how our supply chain can not only know about this technology, but how they obtain this helmet and maintain it properly.

JD: The MIPS technology seems to work very well in other areas, such as cycling and winter sports. Before now, I don’t think all of us in the construction industry were fully aware of how the body and head behaves during a fall. So, it’s important that we transfer any lessons from other industries and areas such as sports, and improve the technology we use. It’s about continual improvement.

MS: I can’t argue with the safety benefits of MIPS. But there is no point in wearing the helmet, spending the money and having that specification, if the chin strap is not done up. I don’t think the site workers have that mentality yet, but this journey has only just begun and I can definitely see a role for the MIPS technology.

GM: I think there are certainly applications where the MIPS technology is a huge opportunity. Comfort is a huge issue though, especially in relation to chin straps, as some of our people are wearing safety helmets for up to 10 hours a day. We should do what we can to make these important pieces of kit comfortable to wear, especially

the chin strap attachment.

Max Strandwitz: Comfort is also a safety aspect because if the helmet is not comfortable to wear on your head, you will not wear it and the same applies with doing up the chin strap. We have done a lot of tests on that and we do not get any complaints on the comfort.

Peter Halldin: The chin strap is extremely important. It is part of the helmet and how we test its ability to protect the wearer. Without it, the helmet will fly away.

Olof Rylander: Weight is related to comfort and the weight of this no-friction layer is only 30 to 50 grammes, so it is not going to add a lot of weight to the helmet itself. One other good thing about the MIPS safety helmet is you don’t need any training for your employees to use it.

GM: We need to think about the psychology. I do worry that a lot of people walk onto projects and there is an assumption that they are never going to be involved in an accident. They are asked to wear a safety helmet, but they see it as just another generic item of kit. We need to change that perception and ensure our people are risk aware and risk competent.

Perhaps a bespoke helmet is given to each site worker with their name on. The product is to an enhanced standard and there is some pride in wearing it. Yes, we might have to spend a little bit more money, but if we are talking about a product that is going to last five years not one, the money will be recouped.

DR: At CoTrain, we recharge our apprentices for the tools that we give at their induction so they take much more care of them – then give a full refund when they qualify. So the sector should also do that with the safety helmet – make the whole thing more personal, so the user really wants to look after it.

SC: Hard hats usually have a shelf life of two years. What is the shelf life of this helmet and is there a different storage process compared to a normal helmet?

MaxS: We expect five years to be the minimum lifespan for the MIPS product. MIPS adds around €20 (£18) to the helmet, so it is quite a low premium to pay for having an added safety feature.

MIPS partners with Centurion

Shortly after the round table, a partnership between MIPS and British manufacturer Centurion Safety Products was announced. Centurion will be launching the UK’s

first safety helmet with MIPS in Q2 2021.

Nick Hurt, CEO of Centurion Safety Products, said: “We are constantly looking at how our products not only meet relevant safety standards but exceed them.

“We are therefore excited to become the first occupational safety brand to incorporate the MIPS cradle rotational impact protection system into our helmets. “The MIPS system will be featured in a version of our Nexus HeightMaster Safety Helmet, which is already a stand-out product thanks to its advanced safety standards.”

This article has been created by Construction Manager in partnership with MIPS.