Attracting much-needed workers with the skills of the future will require construction improving its image and making itself more appealing to young talent, writes Pablo Cristi Worm.

Over the past couple of months, the new Labour government has set out its policy agenda and its ambitions for major new programmes, from housebuilding and planning reforms to energy generation and transmission. One important question is where our sector will find the resources to deliver these goals. As of 2024 Q1, the number of construction workers reached 2.08 million, falling below the pandemic trough.

Two elements of the persistent construction capacity crunch are the historically high levels of contractors’ insolvencies, which stood at 1,154 companies in Q4 2023, and the severe shortage of skilled workers, with vacancies 38.5% above pre-pandemic levels.

To achieve the nation’s ambitions for growth, policymakers and industry leaders need to address these issues. In particular, they must figure out how to attract new and different skills to the sector.

There are many risks from a lack of capacity: the dwindling pool of construction companies, coupled with a shrinking workforce, leads to less competitive pricing strategies on the one hand and to higher wages on the other. In turn, this exacerbates tender price inflation and the costs of major programmes.

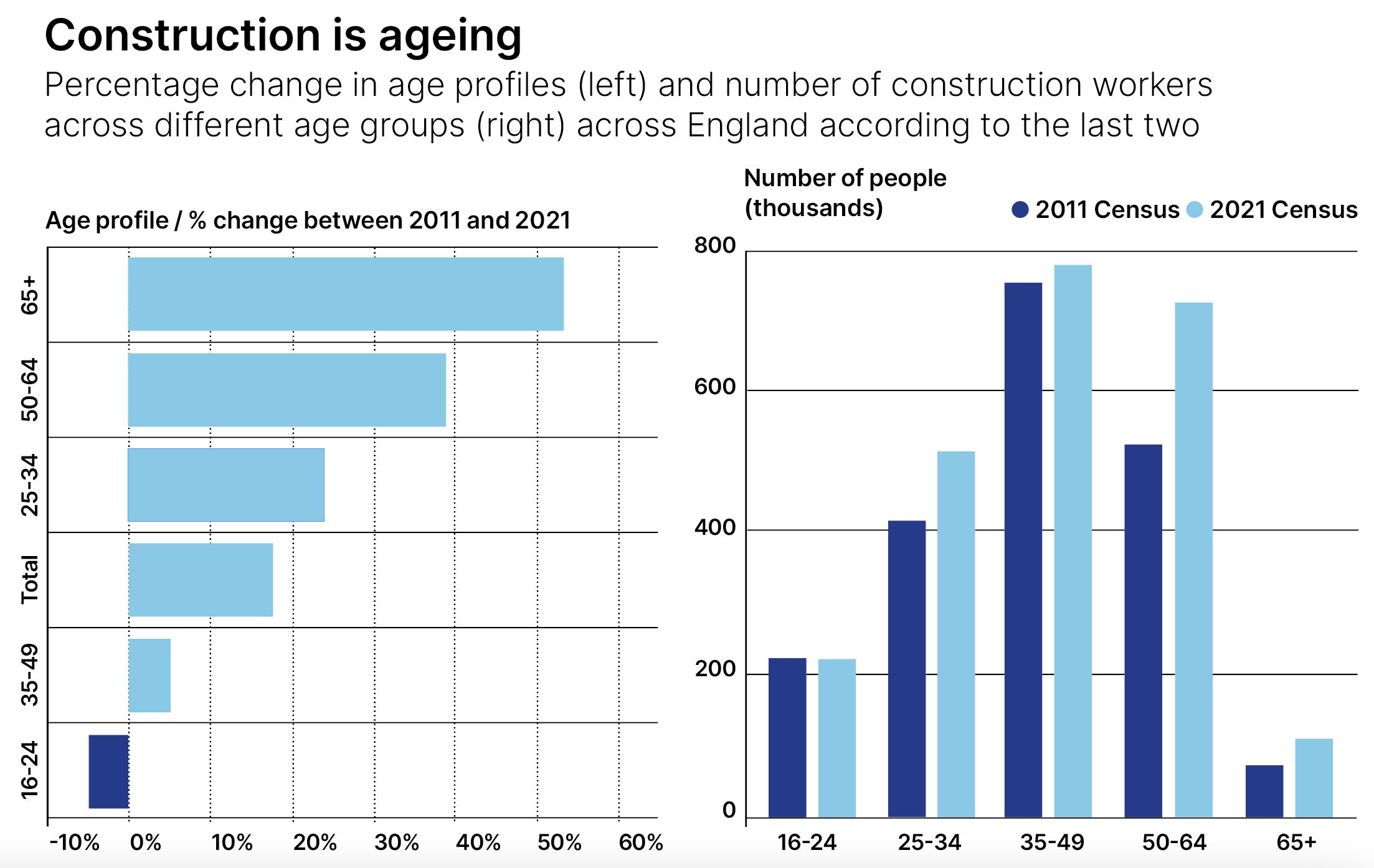

Sector age profile

The industry’s ageing workforce has long been a concern. A substantial portion of experienced workers are nearing retirement, and the number of young people entering the sector is declining, leading to a potential loss of invaluable expertise.

This was historically mitigated by a high level of migrant labour. Yet the UK’s departure from the EU after the 2016 Brexit referendum has resulted in a sharp reduction in skilled workers from the continent. Between Q4 2019 and Q4 2023, the industry lost around 14% of its UK-born workforce. In addition, three-quarters of EU construction workers lost due to post-Brexit restrictions were aged between 25 and 39.

According to a future of work survey by international law firm Osborne Clarke, only 15% of workers in the built environment sector intend to continue working in some form after retirement, compared to a 27% cross-industry average.

However, the changing nature of the skills we need in the industry is now just as important, if not more. Solving these issues will require us to improve the perception of construction and make it a more attractive career path for a diverse range of talented entrants of all ages.

Cutting-edge construction

Part of the problem is the mismatch between the skills taught in educational institutions and the practical demands of the construction industry. Plus, the economic turbulence of the past years has only made it more difficult for firms themselves to invest in people. This is particularly true when it comes to the increasing digital demands of construction.

Neglecting to familiarise students with the latest technologies not only means they’re less prepared for the working world, but it also fails to show them the truly modern, digital face of construction, which may help to widen the appeal of careers in the sector.

Targeted training programmes and apprenticeships, as well as upskilling existing teams, will be crucial to bridge this gap, guarantee a qualified workforce and show the breadth and appeal of skilled roles across the industry.

Now is the moment to act. Construction is experiencing a period of economic growth, with forecasts predicting modest but steady improvement, and areas including housebuilding, data centres, life sciences and energy likely to receive a boost from new government commitments.

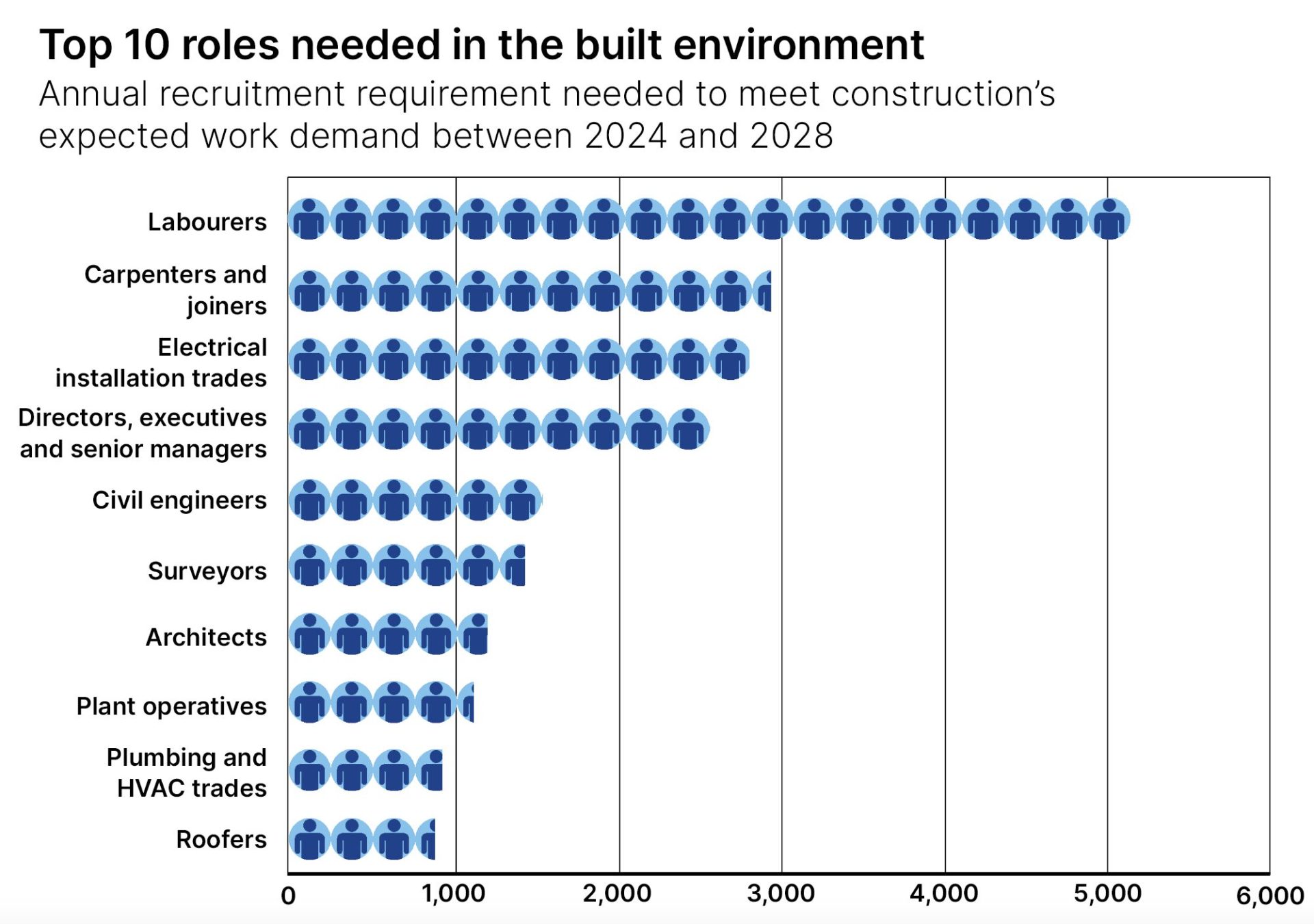

According to the Construction Industry Training Board, the industry will require an additional 251,500 workers to meet expected work demand by 2028. With the creation of the new Skills England body and reforms to the apprenticeship levy coming forward, there’s an opportunity to attract a new generation of talent.

The industry must transform its image – showing its dynamism and its range of digital, technical and environmental aspects. This will help to show that construction offers rewarding and fulfilling career paths in a range of areas and disciplines and will attract the new talent and creative minds that we’ll need to thrive and deliver growth.

Pablo Cristi Worm is an associate economist at Turner & Townsend.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Ageism is also rife in the construction industry, if you have come up through the ranks and not got a degree of some sort then unfortunately when you reach the ripe old age of 60 with 40+ years experience your job prospects start to dwindle and your CV, especially with automated inspections, doesn’t get a look in.

Pablo’s statistics are correct but, as an economist, has he ever stood on a scaffold on a January morning when the wind blows hard in your face and your task seems impossible but has to be done? Construction is a tough job! We need employers and the government to make retention of skills a priority!! They could relax, or abolish, the way that tax is collected and allow flexible working after a tradesman retires. They would have already paid their NI so that is not a cost. Employers could have an elder HR specialist that could match the company’s needs against rejected “too old” CV’s. I am nearly 80 but work 3 or 4 hours a day for 3 or 4 days a week on my own projects. I am sure there are HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS like me who want to earn a little, pass on ‘tricks of the trade’ and fit it around my other obligations. Then we don’t have a shortfall, we have inter generational respect and continuity.

Pablo needs to mention that whilst the government is seeking to retain skilled workers there is an industry quango, the Construction Skills Certification Scheme (CSCS), that is hemorrhaging workers out of the sector in its thousands with its cessation of Industry Accreditation (IA), policy for skilled artisans.

Twenty years ago young people training for construction careers in local colleges couldn’t complete their courses and get qualified because they couldn’t get the necessary work experience.

This is being repeated in 2024 – a friend’s nephew can’t complete his electrical engineering course because he can’t get the necessary work experience and on-site training.

And skills shortages seem to be a surprise to some.

I agree with Michael Norton re CSCS. It has taken me 4 months and endless complaints to finally get my replacement card. If I wasn’t so pig headed I would have just walked away. There must be thousands with expired IA cards in the same position

I, like many who took early retirement, soon find they might like to return to work but on a part time basis. However, there are zero jobs advertised giving part time as an option.

What nobody appears to be mentioning is that some companies only want specific skills rather than a fully skilled workforce, therefore one/two components I once asked someone (who was supposed to be a carpenter/joiner) to go and fit a new door and frame at a property. His reply was “I’ve never fitted a door and frame”. I asked, “how come”? His reply was “I’ve only fitted kitchens”. The other problem is a lot of “construction” workers are self employed (i.e. one man band) and can’t/won’t take on apprentices because they can’t afford to take the time to train them (because they need to keep their prices down to win work/contracts). And then there is the “political” element, the first industry to suffer cuts are construction and therefore lack of job security. Governments need to wake up and offer better job security in hard times.