Home of World War Two’s codebreakers, Bletchley Park is constantly looking for new ways to tell its stories. Kristina Smith talks to head of site works Phil Atkins about the conservation and new build projects on the famous estate.

When the board of trustees at Bletchley Park advertised for a head of site works in late 2015, there can’t have been many who could have fitted the bill. They were looking for someone who could manage the FM and maintenance team, the landscaping team of salaried staff and volunteers, and someone who could project manage an ongoing programme of capital works. They even wanted the candidate to have CAD skills.

Step forward Phil Atkins, whose unusual career path now seems almost tailor-made for his job at the former workplace of codebreakers such as Alan Turing during the Second World War.

A graduate in rural resource management, it was a part-time job at a self-storage store while studying that led him to work for multiple firms in that sector, which he followed with stints at contractor Rok and offsite building manufacturer Terrapin and then various facilities management roles.

Diverse job description

Atkins recalls coming across the job advert on Bletchley Park’s Facebook page, which he was following as a local resident and visitor. “I thought ‘that’s quite a diverse job description’. I could join the dots between my experience and the job here,” says Atkins. “Then I did everything in my power to make sure I got the job.” The day of his interview, he was offered the role.

Almost eight years on, Atkins is proud to have successfully delivered Bletchley Park’s most recent capital works programme: a £14m, three-phase affair which has seen wartime buildings at the heart of the site opened to the public for the first time. They have been repurposed as exhibition spaces, another turned into a collection and archive store and the creation of a learning centre including the construction of a beautiful new auditorium.

Two local contractors have delivered the works, Neville Special Projects and Edgar Taylor Construction, both of which are headed up by MCIOBs: Simon Last and James Taylor respectively.

Getting the job right goes beyond personal satisfaction for Atkins and his colleagues. It is about ensuring that the Bletchley Park story continues to be told to future generations through the way the buildings are cared for and repurposed. “We all have an awful lot of pride in working here,” he explains. “It is like a family. People become wedded to the conservation and the preservation.”

A fight for survival

Walking around Bletchley Park, the link between the work done here during the Second World War and today’s big-data opportunities and threats are striking. It’s hard to believe that this place’s future as a museum has been in jeopardy.

Back in 1990, having been home to a teacher-training college and a headquarters for the local GPO, there were plans to demolish the site and redevelop it for housing and a supermarket. The Bletchley Park Trust was formed in 1992 in response. Then in 2011 the Trust was able to secure a £4.6m grant from the National Lottery. Along with the support of a variety of a wide range of trusts, companies and individual donors, and the work of many people, this was a major step forward in securing the future of the site.

The Trust was able to restore and open the original wartime codebreaking huts, and restore and convert one of the wartime blocks into its visitor centre. In 2014, the same year that the film The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing, was released, the revived Bletchley Park was opened by the then HRH the Duchess of Cambridge, whose grandmother worked here during the war along with her twin sister.

Since 2016 when Atkins arrived on site, there has been a series of projects, opening up more of the site to visitors.

Project management skills

“Project management was one of the key skills that the Trust wanted when they employed me,” says Atkins. “As an in-house project manager, I am a lot closer to the coal face and constantly talking to the contractors. I am in the thick of it most of the time, in my hi-vis and covered in dust. I also get to see how the build evolves and to understand how it’s assembled and have the chance to influence fixtures and fittings.”

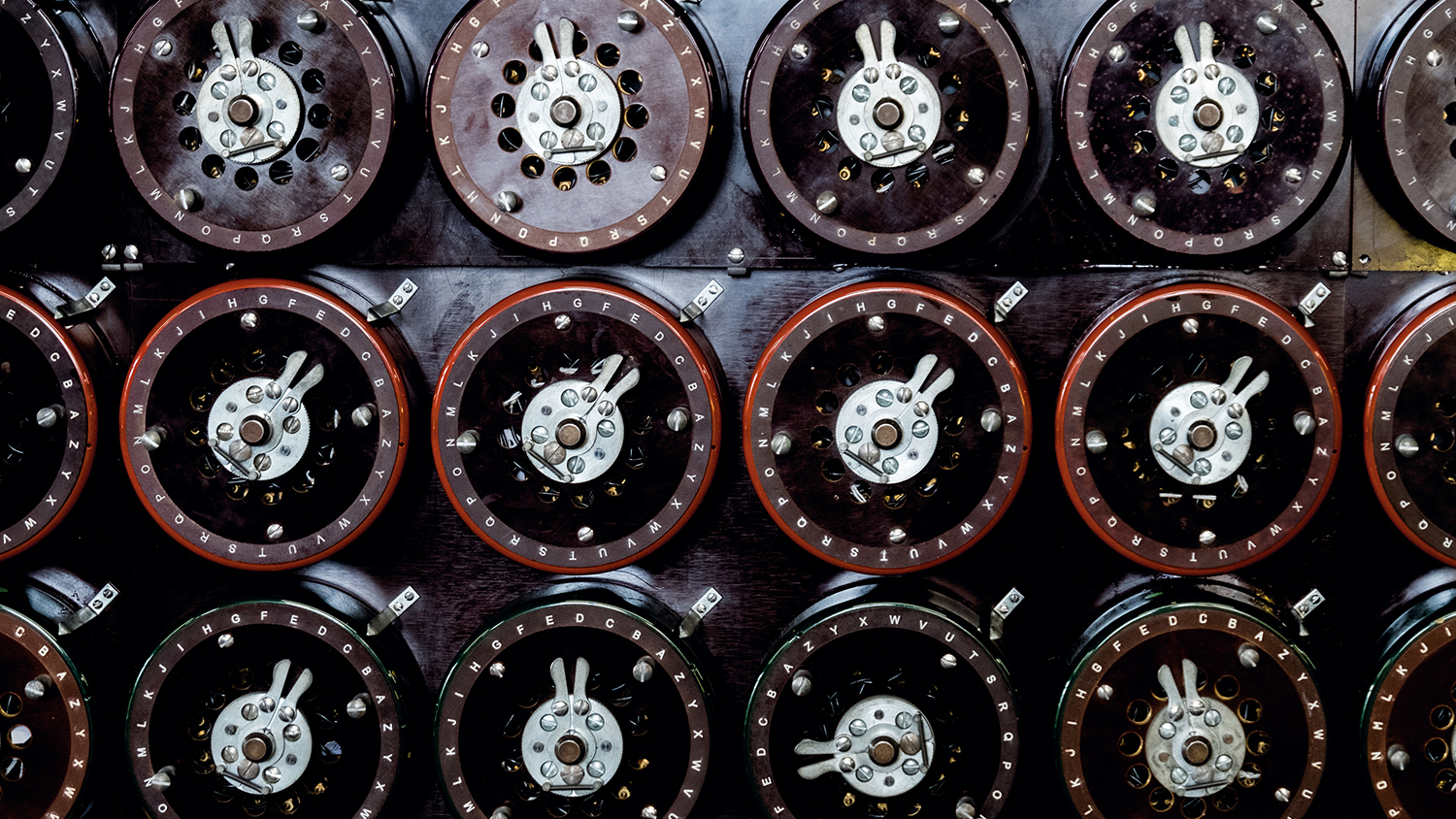

The first project Atkins oversaw involved modifications to Hut 11A to house an exhibition about the Bombe – invented to speed up the breaking of the Enigma cipher – which required an upgrade of the building including the discreet introduction of air-handling plant.

Next came the refurbishment of the Teleprinter Building to house the D-Day: Interception, Intelligence, Invasion exhibition. Opening in April 2019, shortly ahead of the 75-year anniversary of the D-Day Landings, this exhibition tells the human story behind the landings.

Each of the three phases of the latest tranche of work was tendered separately, and went to local contractors, which Atkins prefers for sustainability reasons. The first two were awarded to Neville Special Projects while the third went to Edgar Taylor Construction.

“The connection with Bletchley Park came through our successful completion of the Story Museum project in Oxford.”

In the first phase Block A was redeveloped to create two exhibition spaces. The first now houses Bletchley Park’s The Intelligence Factory exhibition, which uses personal stories and exhibits to explain how a mind-boggling 9,000-person workforce was deployed. The second provides a controlled environment for visiting exhibitions and is currently home to The Art of Data: Making sense of the world, which showcases visualisations of data then and now.

Preservation challenges

Walking around Block A, Atkins points out some of the challenges in preserving the original aesthetic while respecting modern building control requirements. For instance, all the cabling for the electrics is surface mounted rather than chased in, an alien concept to the electricians.

Achieving adequate fire protection was another conundrum since the steel columns of the building are encased in chamfered concrete.

Although the blocks were erected fast, to house the growing workforce of codebreakers, they were robustly constructed, says Atkins. At the time when the site was chosen to be the Government Code & Cypher School (GCCS), a developer was planning to build housing there and it was he who went on to construct the blocks.

A major hurdle for any works at Bletchley is how to maintain the character of the buildings while making them accessible.

“We have to do it as subtly as we can. Our aspiration is to achieve BS 8300 (Design of an accessible and inclusive built environment), which is very difficult, but we certainly push further than Document M requires,” says Atkins.

“In historic buildings you can negotiate your way out of some of the accessibility rules, but that’s not desirable for us. We don’t want our visitors to find they can’t access parts of the site or have to call up to find out which bits are accessible.”

Wide doorways

In Block A, Atkins, with advice from the Centre for Accessible Environments, decided to cut wide doorways between rooms to allow people using wheelchairs or walking aids to move freely. As Atkins indicates one of these doorways, a visitor using two sticks walks through it, underlining the sense of the decision.

The second phase of the programme saw the refurbishment of an extension to the wartime Teleprinter Building. As well as housing Bletchley Park’s 420,000 artefacts and documents, it has a working area where volunteers are currently digitising the entire archive.

“This was quite a quirky building,” explains Atkins. “They built it as a single storey then, as they topped it out, they decided it was not big enough, so they added another storey. It has 13-inch-thick walls; the idea was to protect the machines.”

Now, the whole building is fire protected for two hours, with one room equipped with an active fire suppression where nitrogen replaces some of the oxygen to create a hypoxic environment in which a fire cannot start.

Learning from history

The final – and most costly – phase of the work was the creation of the Learning Centre. Unlike the other two buildings, Block E had been in use, with space let out on a serviced office basis. It also incorporates a brand-new building to house the 250-seat lecture theatre.

There are eight classrooms within the Learning Centre, each with a different colour scheme. The buildings have been taken back to brick and block, with acoustic rafts to absorb noise. In a larger room, designed for events and adult learning, there is a beautiful modern large-plank parquet floor.

Local contractor Edgar Taylor, based in Buckingham, delivered phase three of the latest Bletchley Park capital works programme – the Learning Centre and new auditorium.

“Most of our work is repeat relationships and the connection with Bletchley Park came through our successful completion of the Story Museum project in Oxford, which was particularly challenging,” says managing director James Taylor MCIOB.

Most of the challenges on this project were linked to the repurposing of the existing buildings, according to Edgar Taylor operations director Bryan Doyle. An early discovery that there was more asbestos than an initial survey had predicted triggered an extensive value engineering exercise, to get the budget back on track.

Working with the architect

Then, when fitting out the classrooms and communal spaces the contractor had to work closely and iteratively with architect Giles Quarme to aesthetically coordinate the setting out of the exposed black service routes with the extensive acoustic features and lighting. The architect wanted the original fabric to remain very visible, which meant that adding an internal acoustic skin was not an option.

The end result is testament to the teamwork and perseverance in getting things just so.

“I am very proud of the quality achieved and that the auditorium looks so much like the original visualisations despite all the VE and financial constraints,” says Doyle. “I think the team has sympathetically repurposed this local building which is of such significant historical importance.”

Next door is the Fellowship Auditorium – named to honour funding support from the Post Office Remembrance Fellowship – which can also be accessed via a reception area which during the war housed two emergency generators.

The Fellowship Auditorium is the last stop on our tour and is suitably jaw-dropping, with beautiful finishes and featuring timber on the floors, walls and balustrades. “I had been looking at it in Revit for such a long time. When it came together in the finishes, it was mind-blowing,” says Atkins.

The Learning Centre was completed before the international AI Safety Summit was held at Bletchley in November 2023 – a reminder of Bletchley Park’s relevance in the modern world and another way to attract and engage visitors.

Bletchley Park history

- The Victorian-era manor house dates from 1883.

- The 23ha site was acquired in 1938 and developed for use by the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) during World War Two.

- The GC&CS team of codebreakers, including Alan Turing, regularly cracked the secret communications of Nazi Germany during the war, most notably the Enigma and Lorenz ciphers.

- Some 75% of the Bletchley Park wartime workforce were women.

- After the war, the site was used by various government agencies, but was at risk of being sold for housing development in 1990, until Milton Keynes Council made it a conservation area.

- The Bletchley Park Trust was set up in 1992 to maintain the site as a museum.

- Visitor attractions include interpretive exhibits, a model Bombe machine, and huts rebuilt to appear as they did during wartime.