Abbey refurb reveals Bath’s hidden history

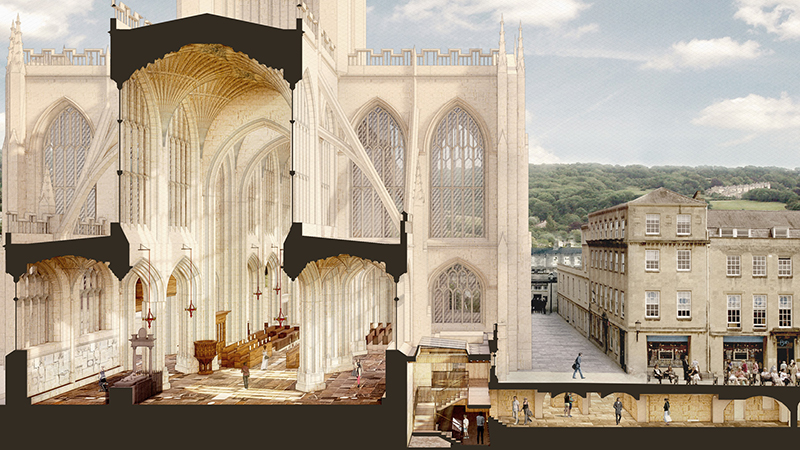

The Bath Abbey renovation works have revealed Roman and Norman archaeological finds, while an ingenious new heating system will make use of the city’s famous hot springs. Rod Sweet reports.

When the city of Bath took on its current form – from the mid-18th to the early 19th centuries – it was rather like a Georgian-era Dubai, with ambitious promoters and developer-architects eager to stamp their novel vision onto this modest town, to capitalise on a new craze for Bath’s hot springs.

As a result, Bath burst out of its ancient walls and acquired the grand character it has today, typified by neo-classical Palladian crescents, circuses, terraces and wide, sedate boulevards. But, nice as it is, this building boom obliterated many physical traces of Bath’s Roman, Saxon, Norman, Medieval and Tudor periods.

Now, an overdue refurbishment of Bath Abbey has prised open a new window onto that history, thanks to the archaeological digs that accompanied it.

Register for free or sign in to continue reading

This is not a paywall. Registration allows us to enhance your experience across Construction Management and ensure we deliver you quality editorial content.

Registering also means you can manage your own CPDs, comments, newsletter sign-ups and privacy settings.

Underfloor heating system

Built between 1501 and 1537, the abbey is a relatively new building. But it sits on the rubble of much older buildings, some dating back to at least 675AD. The finds have been described as “once in a lifetime” for the archaeologists, and include Roman roads, Saxon burials and an exquisite tiled floor that graced the 11th century Norman cathedral which once stood on the site.

The refurb will accomplish something else of both practical and symbolic importance. Every day, a million litres of hot water emerge from deep in the ground just yards from the abbey. Thanks to a solution worked up by engineer Buro Happold, the restoration will replace the abbey’s Victorian-era heating system with underfloor heating powered by the hot springs (see box).

Bath Abbey restoration

Value: £19.3m

Programme: May 2018 to early 2021

Client: Bath Abbey

Contractor: Emery

Architect: Feilden Clegg Bradley

M&E engineer: Buro Happold

Structural engineer: Mann Williams

Some years ago, Bath Abbey – a parish church and a busy venue for performing arts – began to grapple with the constraints created by the deterioration and inflexibility of its physical spaces.

Of chief concern was the floor, which was in the midst of a slow-motion collapse thanks to thousands of bodies decomposing under the stone slabs, called ledger stones.

Over the centuries, around 7,000 individuals had been interred in the 2m-deep space, mostly full of soil and rubble, that lies between the existing abbey floor and the floor of the Norman cathedral beneath it. The ongoing decomposition of the bodies created voids, leading to the sloping and sinking of the ledger stones, explains Alix Gilmer, project manager for the Abbey.

“Apart from the structural problems this could cause in the long term, the uneven floor was also difficult for people with mobility problems and for people in wheelchairs,” Gilmer says.

Other issues included the building’s antique heating system and a lack of space for basic amenities such as toilets, cloakrooms and catering.

Working with architect Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, the Abbey hatched the £19.3m restoration project, which it dubbed ‘Footprint’. This would fix the floor, install underfloor heating and create new spaces in the vaults and neighbouring Kingston Buildings, Georgian-era townhouses where a ‘discovery centre’ will be located.

Keeping materials flowing

Work commenced in May 2018, with local contractor Emery moving onto site. Emery has had to keep the church open throughout the project, and keep quiet during Holy Communions, while managing the logistics of a tight site in central Bath, keeping personnel and materials flowing to and from many different micro-work faces. The contractor also needed to work around the 18-strong team of archaeologists.

To fix the floor, Emery had to move out the pews, then lift the 891 ledger stones covering an area of 1,000 sq m.

These stones weighed up to 400kg apiece and were themselves of historic interest because they are inscribed with names, dates and other details pertaining to people of note buried under the floor from between 160 and 350 years ago.

Because of the pews, many ledger stones had not been seen for more than a century, so the Abbey trained a team of volunteers to decipher and record the inscriptions, and to research the life stories of the parishioners they describe in order to bring them alive, as it were, for visitors.

With the stones off, workers could remove a layer of the material underneath, plus the old cast-iron heating pipes, and pack in the voids that had formed. That allowed them to pour a reinforced concrete slab and lay pipes for the new heating system, before relaying the ledger stones on a firm foundation.

“By the end of the project,” says Emery site manager Felix Emery, “over 1,000 cu m of material will have been excavated by hand from inside the abbey alone, most of it containing disarticulated human bone that is removed and retained.”

Some of the human remains were reinterred, and some relocated to the abbey cemetery south of Bath. “It has been very important to the Abbey that this has been done carefully and respectfully,” says Gilmer.

As excavations progressed, many layers of Bath’s history have been uncovered, dating back more than two millennia.

Like any city with a 2,000-year history, repeated cycles of construction and demolition have raised Bath’s ground level.

The Mesolithic-era level – the Stone Age – requires digging around 4m down, says Cai Mason, of Wessex Archaeology, who led the digs in the abbey floor.

That was where the archaeologists team found the two Roman roads, hard, rammed-gravel surfaces – the most common Roman paving technique – with carved stone guttering laid along their edges.

“It’s very, very hard,” says Mason. “You need a pickaxe to get through it. These are properly engineered roads, among the first structures on the site.”

Saxon-era buildings

Up from the Mesolithic-era level, at a depth of 3m, the archaeologists found the remains of two Saxon-era buildings. They are stone apsidal structures – semi-circular ends to rectangular buildings – about 3m in length and 1.5m thick, and the first-ever physical evidence discovered of the Saxon monastery indicated by historical records, which stood on the site. The masonry construction signifies high-status structures, Mason says. Lime plaster containing charcoal allowed the archaeologists to radiocarbon date the structures to the ninth century.

Another metre up, and the archaeologists uncovered the floor, laid in the 1300s, which covered the entire Norman cathedral that preceded, and dwarfed, today’s abbey. One of a string of eye-popping structures built by the Norman conquerors to stamp their power on England, the cathedral was Romanesque in style – thick-walled, small-windowed and heavy-shouldered – and 100m in length. Previously undiscovered sections of the cathedral’s walls were also uncovered.

“Stylistically, it was a copy of the Basilica of Saint-Sernin in France, which is the same ground plan that the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela [begun 1075] is based on,” says Mason.

Floor reconstruction works

By the late 15th century the Norman cathedral had fallen into disrepair, and the new Gothic-style abbey church was commissioned in 1499, completing just in time to be shut down in 1539 by King Henry VIII in his war on the monasteries. But it stands proud today as an iconic feature of the city of Bath.

The first phase of the floor reconstruction works, at the east end of the abbey, completed in June 2019, with the north phase finishing in March. Work has also involved refurbishing the Kingston buildings and excavating the vaults, while shoring them up with additional concrete supports.

The third and final phase is due for completion by the end of the year. Emery will then install a new lighting system and reinstate historic furniture in the first months of 2021, as the new abbey facilities prepare for opening to the public.

Warmth springs eternal: the abbey’s new heating system

Buro Happold’s closed-loop heat exchange system makes use of the city’s springs

Buro Happold has designed a heat exchanger to draw energy from Bath’s hot springs. The restoration has not just revealed some of Bath’s underworld past; it will put that past to good use.

The springs were first discovered around 863BC. Bubbling up from depths of up to 4km, more than a million litres of water emerge at 46°C every day, just a stone’s toss from the abbey’s front door. It spends time in various pools before the overflow travels through the Great Drain, a tunnel dug 7m below ground by the Romans, big enough for a person to pass through, before spilling into the River Avon 400m away.

The spring water is not suitable for underfloor heating, owing to its high mineral and silt content, and risks from pathogenic amoeba.

But engineers at Buro Happold discerned that the Great Drain passes close enough to the abbey to allow a closed-loop heat exchange system. This can extract 160kW of energy from the hot spring water in the Roman drain, enabling heat exchangers to provide separate water at 20-25°C to the abbey’s electric heat pumps.

The pumps will then raise the temperature to 50-55°C, suitable for underfloor heating and trench heating during milder weather.

By going back to the first century, Bath Abbey can more comfortably proceed into the 21st and, for the first time, two of Bath’s most visited monuments – one dedicated to the body and the other to the soul – will be working together.