Stately home Wentworth Woodhouse is undergoing a £200m restoration and CIOB member company William Birch & Sons is one of the companies involved. Kristina Smith reports.

Wentworth Woodhouse, stable block renovation

Client: Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust

Contractor: William Birch & Sons

Architect: Donald Insall Associates

Cost: £5.1m

Programme: April 2023 to November 2024

Form of contract: JCT with contractor’s design portions

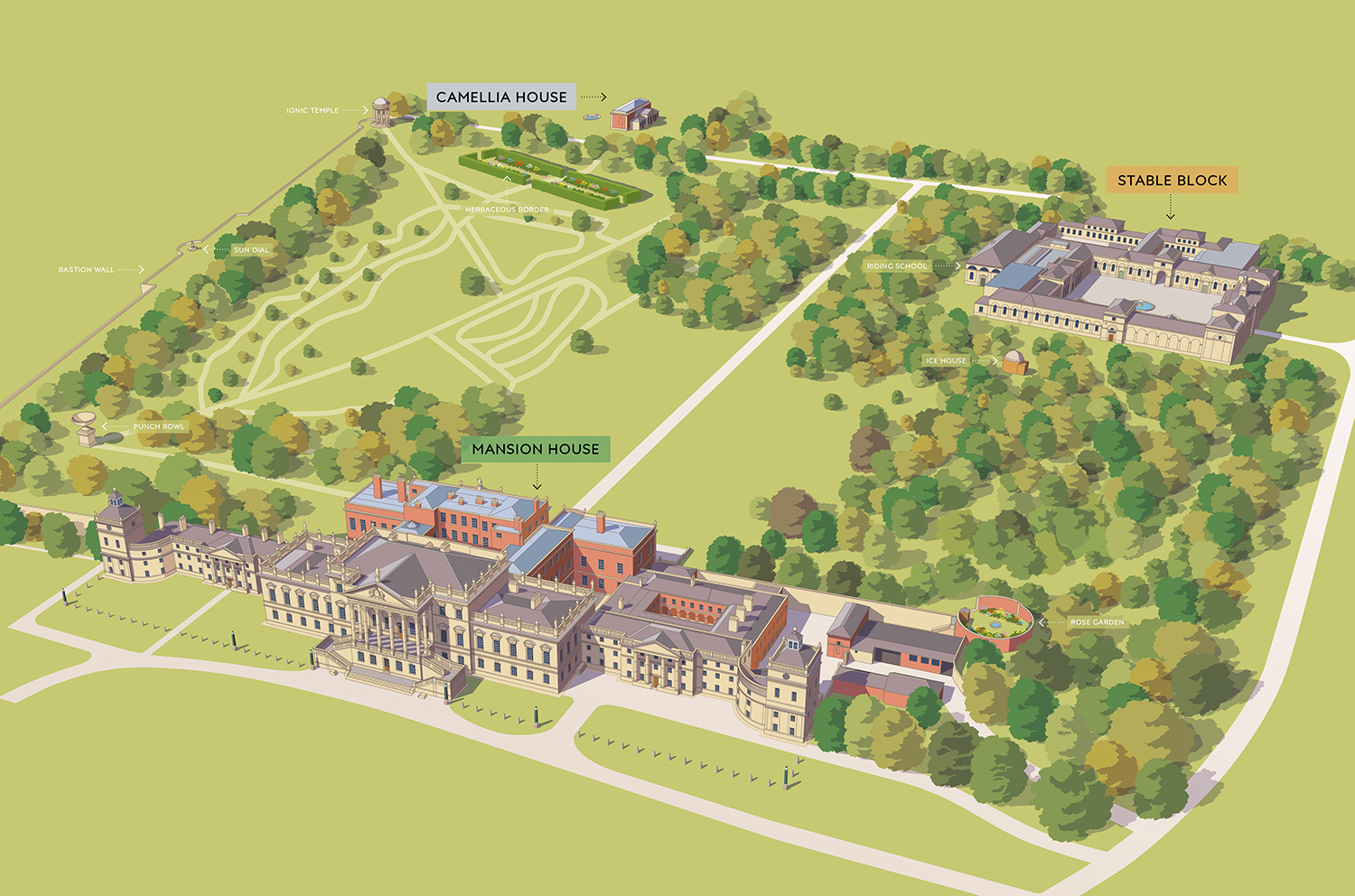

Wentworth Woodhouse is one of the UK’s grandest stately homes. Built with the Rockingham family’s wealth from South Yorkshire coal mining, the country estate near Rotherham consists of the main mansion house, with its 17th century core, stables, a riding school, workers’ cottages and a garden tearoom.

But when the coal industry’s fortunes declined last century, so too did those of the Rockingham family and Wentworth Woodhouse fell into disrepair. Now under the control of the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust, set up in 2014, the estate is undergoing a £200m restoration programme.

“You only have to look at Blenheim or Chatsworth to understand that heritage buildings like these are huge economic generators for their regions,” says trust CEO Sarah McLeod. “Wentworth Woodhouse will have the same sort of impact, and more than pay back what we are investing in it.”

This is a massive project. The mansion house has more than 300 rooms, with 23,225 sq m (250,000 sq ft) of floorspace, and covers an area of more than 1ha (2.5 acres). It is surrounded by a 73ha (180-acre) park, and an estate of over 6,000ha (15,000 acres).

Every Friday morning, McLeod reviews a 50-strong project list. Currently her team is working on a bid that will see a £28m contract let to complete around half the Grade I-listed stables, another for the installation of a lift in the mansion house and some restoration works on the chapel.

Perhaps her biggest challenge is raising funds for the transformation, which has come from Historic England, the National Lottery Heritage Fund and the Levelling Up Fund, plus private donors and trusts.

Scheduling the projects, while carrying out any maintenance and urgent repairs, is a juggling act. “The priorities of the projects change because sometimes funding becomes available that would suit a certain project,” McLeod explains. “Also, the conditions of the buildings change. If we discover a real problem, something else moves higher up the list.”

Delivering the project

CV: John Hutton, project manager, William Birch & Sons

After studying on the Construction Industry Training Board’s (CITB’s) Youth Training Scheme, John Hutton was taken on by Sabre Kean to do an apprenticeship.

After a few years’ bricklaying, his dad, an electrician, persuaded him to study for an HNC in Building Studies at night school and by 24 he was running a small housing refurbishment job. “I didn’t sleep for a month,” he says.

The first part of Hutton’s career was spent on a variety of new-build projects for regional contractors. Then, in 2013, a former colleague enticed him to work for William Anelay on a project to restore Sheffield Cathedral. When William Anelay went out of business in 2016, he joined William Birch.

“I enjoy building but moving into restoration was a breath of fresh air,” says Hutton. “I had done lots of new-build school extensions and industrial buildings which are all quite straightforward. This was more challenging. I’ve loved every second of it.”

Since moving to William Birch, Hutton has worked on significant heritage projects including the Mansion House for the City of York, Hylton Castle in Sunderland, Whitby Abbey Visitor Centre and Cowick Hall in Snaith.

John Hutton image: Matt Roberts

CIOB member company William Birch & Sons is one of the companies involved in the restoration works. When CM visits in July, the contractor is working on a £5.1m project to create commercial kitchens in one corner of the stable block.

This is the second capital project from the trust’s ambitious masterplan. The first one, also delivered by William Birch, was the £5m restoration of the Camellia House which is now a tearoom and event space (see box, this page). Prior to that, the trust had spent around £7m on repairs to the mansion house’s roof, to make it watertight.

William Birch began work on the current stables project in April 2023, starting with demolition and strip out. The buildings had been altered to accommodate a PE college between 1950 and 1977.

“They were not very sympathetic. There was no professional industry guidance in those days to provide direction,” says William Birch’s project manager John Hutton. “We demolished a big part of the work from that time and are making good some of the other previous work.”

William Birch is delivering the project under a framework agreement for the stables and worked with the trust to value engineer the project and meet its initial budget. The project grew when funding from Historic England came through to repair the roof and masonry on the Mews Court cottages, right by the stable block, which was added to the contract through a variation.

Rotten timbers

Neglected for decades, the stable building’s roof needed extensive repair work. When the scaffolding went up externally in July 2023, with an internal crash deck, Hutton found rotten timbers and structural problems. “You could stick your finger through the timber like a hot knife through butter,” he says.

Repairs require high levels of skill, with timber salvaged from beams and trusses that have to be removed saved to patch up other elements. Hutton pays tribute to heritage joiner Joe Woodmass Joinery, whose work on the project includes the creation of new king trusses, built exactly like the existing ones were over 200 years ago.

The sash windows are also being repaired and reglazed on site, where they can be. New sash windows are coming from Germany, with a 16-week lead time. Glass for the windows will be Histoglass, which gives higher U-values than traditional single-pane glass to reduce heat loss.

Westmorland slate for the roof repairs was salvaged from the reroofing of the main house.

“It’s an expensive product and it’s difficult to get in large sizes,” says Hutton, going on to explain that the practice in the 1700s was to start with large slates, 600mm or 700mm long, at the bottom of a roof, with sizes diminishing as the roofers worked upwards.

Kitchen extension

The project also sees the construction of an extension for the kitchens, designed by architect Donald Insall Associates, to replicate as closely as possible a building that was demolished in the 1950s or 1960s. The upstairs level of the extension will eventually connect to the riding school, which will have a mezzanine floor added. William Birch built sample panels with sandstone from four different quarries so that the architect could select the one that matched best, settling on stone from Morley near Leeds.

Internally, timber partitions have been installed to protect the walls of the building, with insulation inserted behind them. “The trust has invested heavily in insulation to improve the U-value of the building,” explains Hutton. “The architects chose wood fibreboard because it is a replica of heritage materials and gives breathability and thermal capability.”

Heat for the building will come from ground source heat pumps, with the plant room located in a cottage nearby. Eventually there will be rainwater harvesting too, although that is not part of William Birch’s scope. Below-ground attenuation tanks will slow the flow of rainwater into the sewer system.

The biggest technical issue for Hutton came when the team uncovered a huge crack running up one of the walls of the building. A fault line runs beneath the estate and all the way under the neighbouring village of Wentworth.

“We had to support the building on temporary works with needles and props to retain the wall above while repairing what was below,” explains Hutton.

Other unexpected discoveries included brick culverts under the courtyard. “These discoveries are not uncommon when we start working on these buildings,” says McLeod.

Finding heritage suppliers

One of the biggest headaches on any heritage job is finding supply chain members who are experienced in heritage, says Hutton. “Heritage masons, joiners and plasterers can be hard to source due to the skills shortage in the industry. And with heritage work there can be a lot of challenges that need bespoke solutions. You must have a passion for it.”

Many of the tradespeople working on the stables contract came with William Birch from the Camellia House project. “The people who are working here all enjoy it,” says Hutton. “It’s a great privilege to work on the next stage of Wentworth’s journey. That’s why we do it.”

Camellia House restoration

When the renovation of the Grade II* Camellia House began, which had been a tearoom for Lady Rockingham, the plan was to remove the 20 camellia plants that were growing there. The camellias, imported around 1800, had long ago burst through the glass roof built to protect them but were still surviving.

Then horticultural experts, brought in by the trust, advised that these were some of the rarest and oldest camellias in the western world. Rather than removing the plants to create more room for the new tearooms and events space, they became the star attraction – and protecting them became a priority for contractor William Birch.

To do that, the contractor built a crash deck above them with light tunnels running down through it and a scaffold falsework with a fine netting over it. They were protected with plastic sheeting during works to remove the lime plaster.

“The camellias are particularly averse to lime, so we had to ensure their complete protection,” says Hutton.

The building was derelict, and slopes significantly – evidence of the open-cast coal mining which had come right up to the house. The roofline retains its slope, telling its history. The extensive rebuilding works also included the installation of a ground source heat pump and rainwater harvesting.

The good news is that the camellias survived their year amid a construction site and are now thriving, protected by a new glass roof. Meanwhile the building, which won a Green Apple Award for Environmental Best Practice in 2023, is also thriving, bringing in money for the trust.

Comments

Comments are closed.

An impressive project but how depressing to see that the replacement sash windows are being imported from Germany – do we no longer have the skills to produce what are very much a traditional British architectural component? We’ll certainly be losing the skills if we are to rely on importing such products.