Image: Dreamstime

New environmental legislation means many projects will have to deliver a 10% biodiversity net gain – likely encouraging an increase in ‘commercial rewilding’

The new Environment Bill became law on 31 December and will oblige many construction projects to deliver a 10% ‘biodiversity net gain’. It is a significant leap forward from the current situation, where developers only have to ‘mitigate’ the impact of their projects.

This will affect any landowner seeking planning consent under the Town & Country Planning Act, for new build or refurbishment. In some cases, developers will be able to achieve the 10% biodiversity net gain on site. However, most projects will struggle to achieve this, believes Jon Davies, head of commercial rewilding service RSK Wilding.

“In practice many developers will need to pay to offset their impact on biodiversity,” he says.

“One option is a reforestation or wetland creation elsewhere in the world. However, the biodiversity metric used by the Department of Environment, Fishing and Agriculture (DEFRA) values offsetting less the further it is from the source of the impact. That’s partly to encourage UK biodiversity improvement following the prime minister’s September commitment to ensure that 30% of land is protected for nature by 2030.

“Local biodiversity offsetting replaces a habitat with a new one nearby. These high-intervention approaches can require significant upfront capital costs, and it is not always easy to recreate specific habitats.”

A less familiar, but more cost-effective and natural approach is commercial rewilding, argues Davies.

“It’s a term often associated with reintroduction of animals like beavers and even wolves but is more commonly a ‘ground-up’ approach, creating the conditions for the land to regenerate itself naturally and be recolonised by insects and plants,” he explains.

Achieving biodiversity net gain through commercial rewilding requires firstly, identification of ecologically degraded land local to the construction project, then employing ecologists and other environmental and land management specialists to design a rewilding strategy for the site that suits its specific conditions.

“The ecologists will advise on the number of biodiversity units – the scorecard used by DEFRA to measure net gain – that are likely to be achieved on the land, plus the carbon credits and other ‘natural capital’ benefits could be accrued from the commercial rewilding,” says Davies.

“Once the strategy is decided, the establishment phase will likely involve stripping the topsoil to remove chemical-laden substrates, creating depressions, bunds and other features to increase the micro-habitats, or blocking drains in moorland to re-wet the land and reawaken dormant peat.

“The perimeter would then be fenced off, and for the next 20 to 30 years the land would be left alone. Ecologists would monitor progress to ensure that the figure quoted for the net increase in biodiversity units is actually achieved by the rewilding plan.”

The DEFRA methodology for calculating biodiversity units is complex. It depends on the biodiversity present on the site, how rare existing habitats are, the current use of the area and the condition it is in.

Davies says the current market value of a biodiversity unit is “around £10,000”, so the creation of 100 units would be worth £1m of biodiversity offsetting revenue over the next 20-30 years. “However, it all depends on the types of habitat being created, land values, or the pricing structure chosen by the relevant local authority if the developer is paying for an offset,” he says.

So how do developers identify land away from their site for commercial rewilding?

“There are many landowners, particularly farmers, who are keen to carry out rewilding work on land that is unproductive and difficult to making a living from,” explains Davies.

“Rewilding has the potential to become an important income stream for farmers, especially given the uncertainty around agricultural subsidies post-Brexit.

“As commercial rewilding gains momentum, some developers may group together to pay for larger rewilding projects, which not only offset current developments but ‘bank’ biodiversity credits to cover future projects,” he adds.

Nottingham’s city-centre rewilding plan

A plan to rewild part of Nottingham city centre was unveiled last month by a landscape architect and the local wildlife trust.

The Broadmarsh shopping centre was left half-built when retailer Intu entered administration last June, and the local council has not yet decided on a future for the site. Meanwhile, Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust has worked with Influence Landscape Architects to reimagine the space with wildlife habitats, reflecting the site’s history as a wetland, while also offering potential for urban farming.

Influence managing director Sara Boland says: “It became apparent in the first lockdown that as more people sought outdoor spaces, our understanding of the social and spatial implications of covid-19 were only just being realised. Open space in cities is often formal and structured and this is an opportunity for a completely unfettered and wild approach to a substantial space.”

She adds that rewilding of urban spaces is more economical when compared to the aftercare requirements of heavily designed landscapes.

Balfour Beatty’s rewilding in King’s Lynn

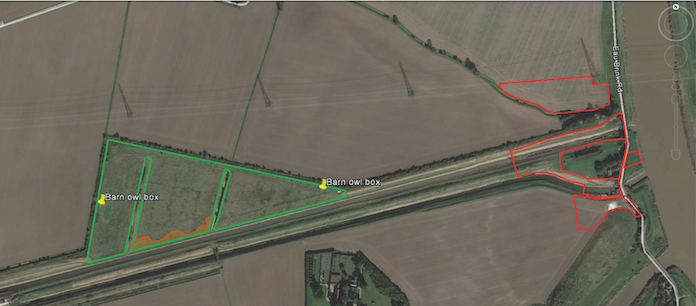

Construction on the Islington pumping station on the River Great Ouse; the rough grassland will be enhanced as part of the biodiversity net gain work

Balfour Beatty is delivering a biodiversity net gain as part of its work at Islington pumping station for King’s Lynn Internal Drainage Board in Norfolk.

Although not a contract requirement, the contractor proposed creating new habitat areas to compensate for biodiversity losses caused by the construction work on the River Great Ouse. The client welcomed the idea.

The initiative involves creating enhanced grassland areas, a reedbed and installing barn owl boxes on a plot to the west of the pumping station site.

Balfour Beatty is using the Natural England Biodiversity Metric 2.0, which calculates biodiversity losses and gains as a result of development or land management changes, to plan and measure the impact of the work.

Location of the biodiversity net gain areas: enhanced grassland (in green); reedbed creation (in orange); barn owl boxes (yellow); plus the location of the pumping station (red)