Nuclear technology has been part of our lives in the UK for over 60 years and provides 15% of our electricity. If government ambitions are realised, we will soon rely on it even more as a source of energy for years to come. But what about disposal of the waste generated? Steve Reece makes his case.

Delivering a safe, secure, and permanent solution for higher-activity radioactive waste is a significant challenge as well as opportunity. Development of a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF) is the only viable, internationally accepted long term solution.

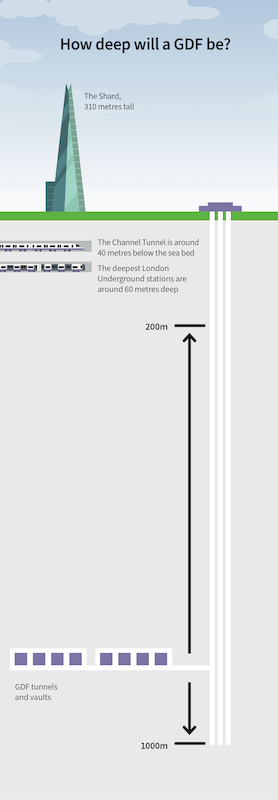

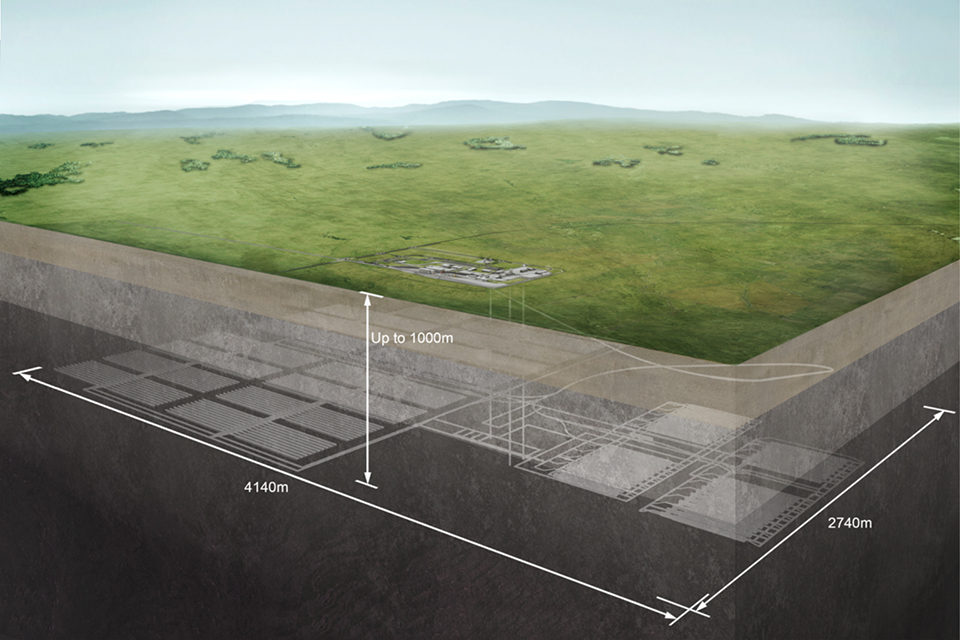

These facilities are designed to dispose of radioactive waste in highly engineered vaults and tunnels. They are housed within suitable geology potentially three times deeper than the UK’s tallest building, the Shard in London.

We expect to have more than 4 million cubic metres of waste to recover and treat to complete the UK’s decommissioning programme. And over 770,000 cubic metres of this will be higher activity waste destined for a GDF.

While radioactive waste can be safely stored above ground this requires ongoing maintenance and needs replacing every 50-100 years. Investing in a GDF now offers a permanent solution for the thousands of years it takes for radioactivity to decay.

GDF has been part of the UK Government’s policy to manage radioactive waste since 2006 and will be one of the biggest infrastructure projects in the UK. Costs are expected to range between £20-53bn.

For the construction industry there will be unique challenges. The depth and extent of tunnelling, coupled with the longevity required to safely store waste is complex.

Challenge and opportunity

This is an opportunity to advance understanding of material behaviour and durability, and to develop overall analysis and design, and drive efficiencies.

This is also a chance to learn more about prefabrication, and modernise methods of construction as the project develops.

Future proofing will be crucial with the project spanning 175 years. It will be a challenge to maintain engagement and manage transfer of knowledge over this period. And in an evolving digital world where the art of the possible frequently changes, design and construction needs to factor in emerging technologies while maintaining safety and integrity.

Identifying a location is another pressing matter. Alongside the British Geological Survey, we gathered broad information about relevant geology across the UK. However, potential sites will require more detailed investigations likely to take 10-15 years.

Community benefit

Equally important is engagement and working with communities. Government policy states a GDF will only be built where there is a suitable site and willing community.

We have already established a dialogue within four communities across Cumbria and Lincolnshire to explore hosting a GDF.

These communities are already experiencing some early benefits, and once a Community Partnership is established, investment of up to £1m a year is injected into the local area.

In the long term, enhanced infrastructure is likely to be required, leading to local and regional improvements. A GDF is projected to create more than 4,000 jobs within the first 25 years, and these roles will bring huge economic stimulus to hosting communities.

Commitment from Government and the sector is also that a GDF should enhance the local environment. This ranges from protection of farmland to enhancement of biodiversity.

Contentious technology

However, the use of nuclear technology can be contentious and, despite advantages, there will always be concerns. Understandably, communities want to feel assured that facilities are safe now and that future generations are also not put at risk.

More than 20 countries are at different stages of GDF consideration and development, including neighbours Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, and France.

Developing a GDF is undoubtedly one of the most ambitious and complex engineering projects of our time. While the hurdles may seem high, a GDF has potential to unlock economic, environmental, and development opportunities for generations to come.

Steve Reece is an engineer and head of siting at Nuclear Waste Services

Comments

Comments are closed.

Nuclear politics aside, it might be wise to start training the mining engineers who will be needed to make this happen as they are in short supply in the UK.