Covid-19 has sharpened concerns about the air we breathe indoors. In this CPD, Paul Williams looks at the mechanical ventilation systems construction professionals should use to tackle indoor air pollution, and the regulations they need to follow.

Ventilation has become a key concern in our buildings. Ventilation has progressed from the primary concerns around condensation and mould prevention, to reducing overheating in the more airtight new homes we began to build in response to the Code for Sustainable Homes, through to addressing the issue of harmful indoor air pollution. Most recently, ventilation is being talked about in the light of reducing virus transmission, elevating the subject to something that the everyday person now discusses and is aware of.

Ventilation and coronavirus

Coronavirus is primarily spread in indoor environments by people breathing in infected droplets and smaller ‘aerosol’ particles in the air that have been exhaled from the nose and mouth of an infected person.

Whilst masks help to limit the spread of these droplets, good ventilation is essential to disperse them. Without ventilation, which brings fresh air into a building, the particles are unable to disperse, lingering in the air for hours and building up over time. The more people that are in an unventilated area, and the longer they spend in that space, the more likely they are to breath in these particles and become infected with the virus.

A short film, released by the Department of Health and Social Care in November 2020, shows how ventilation can reduce the risk of infection from coronavirus by more than 70%, as fresh air dilutes the particles. The video focuses on natural ventilation through opening windows, but also acknowledges the role mechanical ventilation systems have to play when used correctly and regularly.

Ventilation and air pollution

Ventilation in our homes has never been more important, but it would be a mistake to focus solely on coronavirus as the only threat to our health. We have been in the midst of a health crisis for some time, caused by pollution in the air we breathe. According to NHS England, 30% of preventable deaths in England are due to non-communicable diseases specifically attributed to air pollution. PM2.5 and NOx are the biggest threats here. This has been sadly brought to the fore by the recent recognition of air pollution as a cause of a person’s death for the very first time in the UK, and possibly the world.

However, much of the focus on air pollution has been on external air, whereas our exposure to air pollution mostly happens indoors, where we typically spend 90% of our time.

Indoor air pollution sources are widespread and vary dramatically from house to house. Sources include cooking, cleaning, fires, candles and even building and decorating materials. Outdoor air pollution features some of the more lethal types of pollution, including NOx, which are tiny particles that can easily enter our homes around closed doors. For reducing indoor air pollutants, experts agree that both source removal and ventilation are key.

Mechanical ventilation’s role in improving the air we breathe

Whilst extract fans in bathrooms and kitchens provide a basic level of ventilation and are low cost, they are only a step above opening a window. Using these fans, replacement fresh air is provided via background ventilators and normal air leakage.

For a more effective solution, that ensures fresh air reaches all rooms in a home and pollutants are directly extracted without losing costly heat from the property, whole house mechanical ventilation solutions can’t be beaten, especially if you opt for a mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) system.

MVHRs combine supply and extract ventilation in one system. They work on the principle of extracting and re-using waste heat from ‘wet rooms’ (kitchens, bathrooms, utility spaces), efficiently pre-warming the fresh air drawn into the building with waste stale air using a heat exchanger. The filtered, pre-warmed air is then distributed around the home, effectively meeting part of the heating load in energy efficient dwellings.

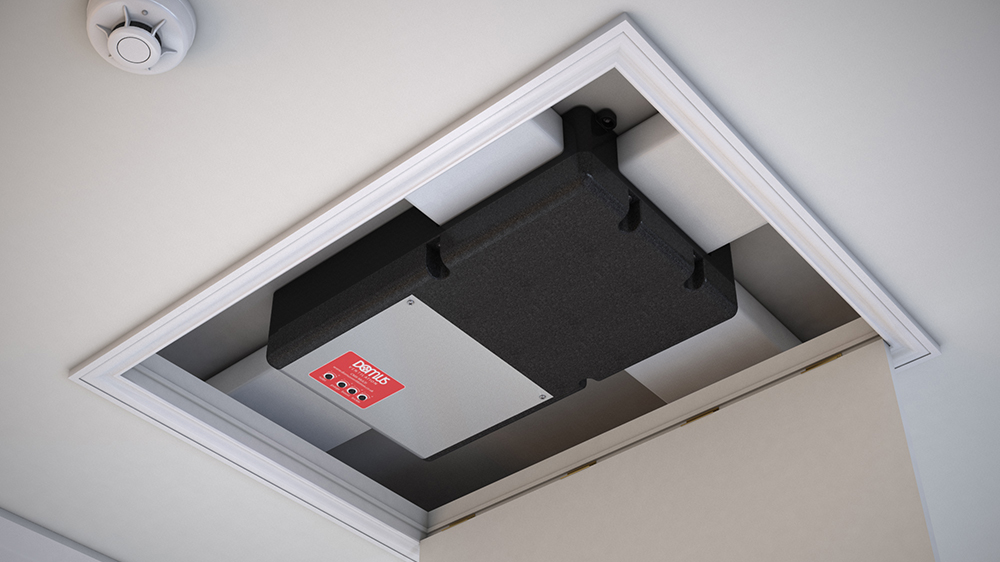

For example, Domus Ventilation’s HRXE-HERA™ and HRXE-AURA™ MVHR units feature advanced heat exchange proficiency enabling up to 95% of waste heat to be recovered. They come with 100% thermal (summer) bypass which automatically activates when the air temperature reaches a pre-set level, allowing cooler, fresh, filtered air in without warming it through the heat exchanger.

MVHR systems provide good ventilation, are energy efficient, and are extremely effective at reducing the risk of virus transmission, condensation and cold air draughts.

But in more polluted areas, such as cities, bringing air into the home also brings in dangerous pollutants, especially if the property is located near a busy road. In these instances, ventilation has to be combined with filtration. The Domus Ventilation NOX-FILT, for example, works on the supply leg of the ducting system of a mechanical ventilation system and prevents up to 99.5% of NO² pollution from entering a home. There are two units in the range with the second one having the added benefit of a PM2.5 pre-filter.

A lower-cost, easier-to-install alternative to MVHR, mechanical extract ventilation (MEV) systems are also available. These actively extract air from wet rooms via ducting to a central ventilation unit which exhausts to the atmosphere. The systems are typically two-speed, providing low-speed continuous trickle ventilation and high-speed boost flow. Replacement fresh air is drawn into the property via background ventilators located in the habitable rooms and through air leakage.

Both types of system have been recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as providing a line of defence against the spread of coronavirus.

Because of the nature of these systems, which require extensive ducting, they are mostly suited to new-build properties. For housebuilders, these mechanical ventilation systems are no longer being seen as ‘nice to have’, but are slowly transitioning to something more akin to life safety systems.

Meeting the Future Homes Standard

Not only do we have issues surrounding air pollution and virus transmission in the air we breathe, we must also be mindful that the Future Homes Standard will result in new homes becoming more airtight to reduce energy wastage. Without sufficient ventilation, however, these homes can become overheated and the air uncomfortable and unhealthy to breath.

Consequently, Part F of the Building Regulations is changing to ensure the right level of ventilation is supplied. This change means all new homes will need to be tested for airtightness and the level of ventilation increased to a minimum of 6 l/s airflow to each bedroom, and an increase in the background ventilation from 2,500 mm2 to 5,000 mm2 in extract-only systems.

One issue that was highlighted when reviewing the regulations is the lack of compliance. To tackle this, ventilation standards have been simplified and whole house ventilation design calculations now only require the number of bedrooms and floor area to be taken into consideration, removing the need to predict occupancy rates, which removes guesswork. This should improve the accuracy of as-built energy calculations to energy assessors.

As part of these changes, reporting has also been tightened up. Now a new style compliance report and photographic evidence must be provided to building control bodies and householders, along with a home user guide specifically for householders.

Paul Williams is product manager at Domus Ventilation.