Construction can still avoid the perils of stagflation. But it needs to improve productivity and combat the skills shortage, says Kris Hudson.

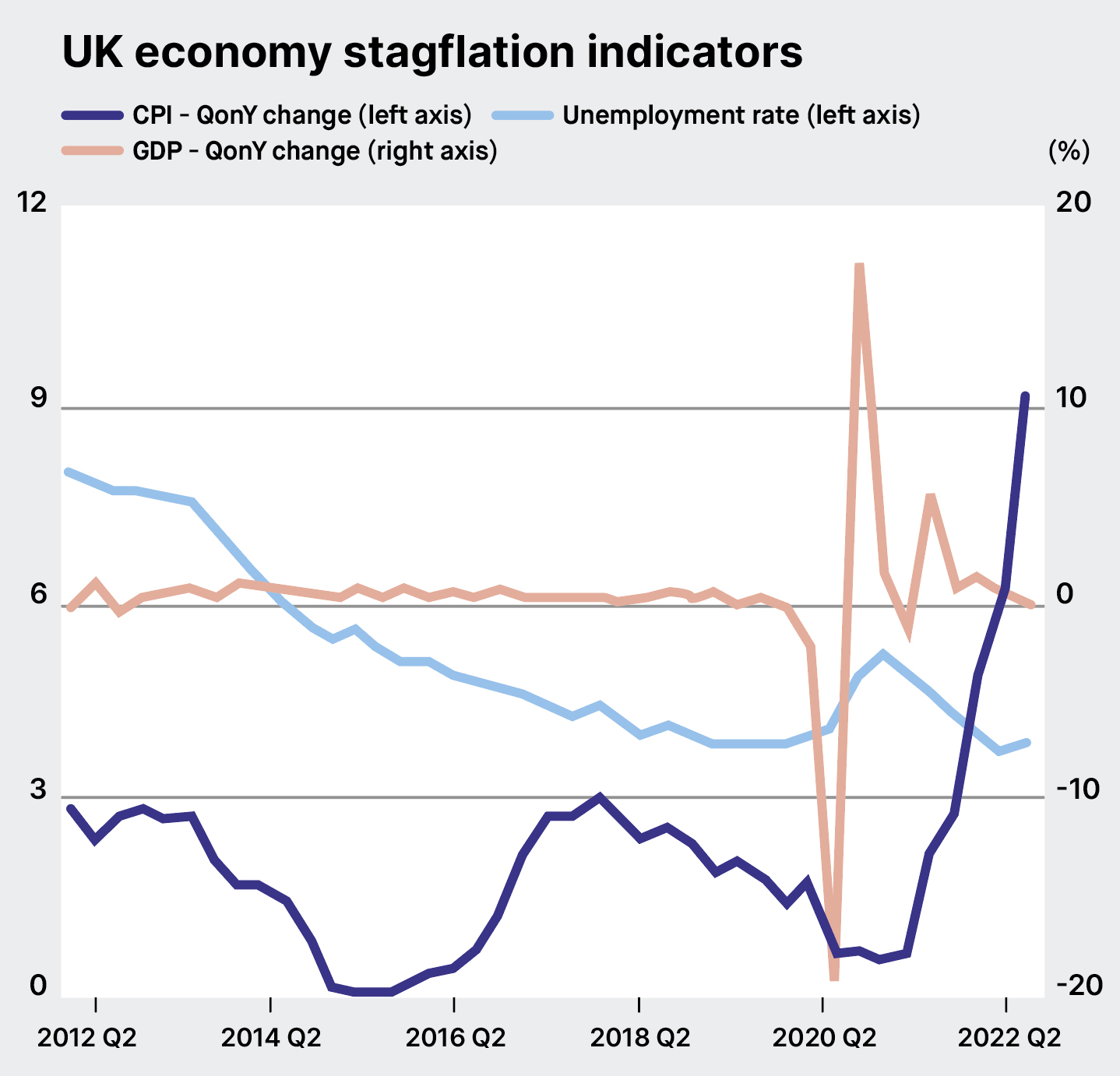

There are worries in some quarters that the UK economy is entering a period of stagflation – a combination of stagnation (low growth and high unemployment) and high inflation.

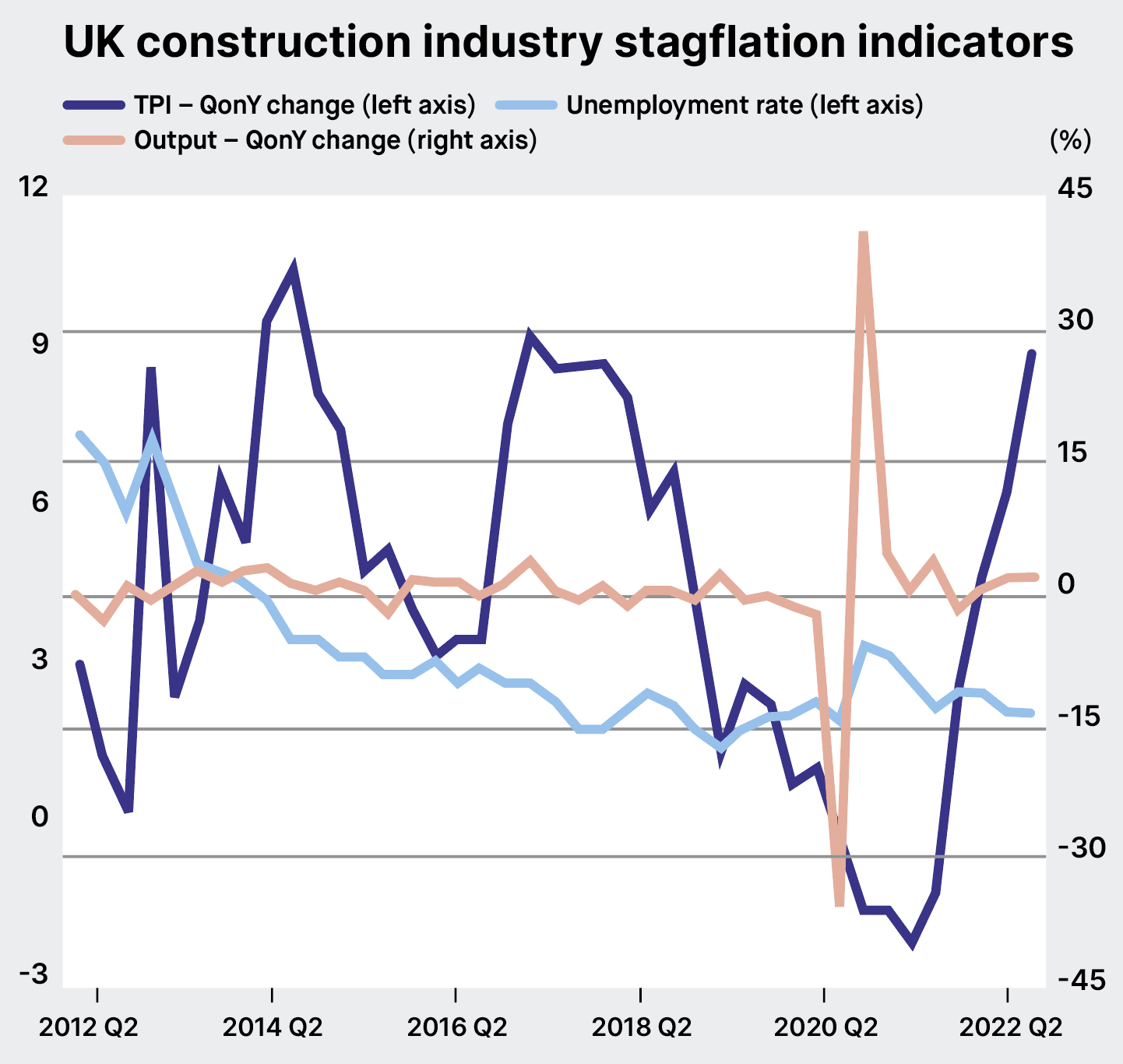

But the ‘textbook’ definition of stagflation has not been reached across the economy as a whole. Nor in the construction sector.

UK inflation is certainly high. The Office for National Statistics has reported a 9.9% rise in Consumer Prices Index in the 12 months to August 2022. Construction tender prices are similarly high. Turner & Townsend’s summer UK Market Intelligence report estimated an average tender price inflation of 8.7% in real estate and 8% in infrastructure in 2022.

Recession potential

Low growth, however, is mixed when assessing stagflation across the UK and construction. Economic growth in the UK, measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), fell by 0.1% on the quarter in Q2 2022. The Bank of England has also forecasted that the UK will enter recession in 2022. Given that slow GDP growth and potential recession often drag down construction output, another stagflation criterion could be fulfilled in the industry.

The figures may be cause for concern. But they don’t alone signal a period of stagflation across the construction industry – for now at least. Construction output remains robust, rising in Q2 2022 by 2.3% on the quarter. In addition to this high output, unemployment is low, getting back to pre-pandemic levels.

Yet, construction activity is weakening. According to the Construction Products Association’s summer forecast released in July, construction output is set to grow by 2.5% and 1.5% in 2023 and 2024 respectively.

Reduced participation

And, while the labour market may remain tight, low unemployment figures for the economy tell a nuanced story and are affected by reduced participation rates. Although low unemployment prevents a typical period of stagflation, UK construction is facing a skills shortage, in part resulting from an increase in workers leaving the workforce during Brexit and the pandemic. This in turn adds upward pressure on labour costs, further impacting inflation and potentially hindering the sector’s output growth.

Construction has a role to play as an important engine of economic growth. Achieving this, while minimising risks to individual firms and mitigating rising costs, will require a laser focus on improving productivity and combating skills shortages with more training and investment.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Clients, architects and engineers must speed up resolving construction issues