On 8 July, the High Court handed down its judgement refusing an injunction sought by local residents to alter part of a new office tower in London, claiming that it blocked natural light to their apartments. Rachel Kerr and Nicholas Levy explain what happened and why this is an important decision for developers.

Rights to light claims from neighbouring property owners are an area of uncertainty in a development appraisal and, at their most extreme, have the potential to disrupt construction on site.

These rights have been under the microscope in the High Court’s recent judgment in Cooper v Ludgate House Limited and Powell v Ludgate House Limited, also known as ‘the Bankside litigation’. Two claims were brought by flat owners seeking injunctions on the grounds of interference with their light against a fully constructed and largely occupied 18-storey office block south of the Thames in London’s Zone 1.

The claimants sought a reduction in the height of the constructed tower or alterations to the rest of the scheme to reduce the impact on their light. Injunctions to modify the block were refused, but damages were instead awarded to the claimants.

Risk-taking and good conduct

There can often be uncertainty about whether a judge would grant an injunction, which is obviously the worst-case outcome for any development project.

In 2014, the Supreme Court in the case Coventry v Lawrence talked of the need for good conduct. However, this is easy to state as a principle but less easy to apply in practice. There have accordingly been doubts about what is required by “good conduct” and what must be done to avoid being criticised for ploughing ahead and ignoring neighbours’ rights.

Helpfully in this case, the judge recognised the challenging reality of urban development and myriad risks faced by developers: “Risk-taking is a necessary part of commercial life and should not be regarded as synonymous with recklessness.”

From a pragmatic perspective, it was seen as unrealistic to entirely de-risk a project before proceeding on site and not an automatic conclusion that a developer is “riding roughshod” over rights by starting works without first addressing and settling all neighbours’ claims.

Where an element of risk remains, the developer’s reasonable conduct forms an essential backdrop against which injuries are examined and risks taken are evaluated.

Calculating damages

An extended period of public engagement on this sizeable scheme, dating back two years before the start on site, accompanied by correspondence and attempts to engage with all affected neighbours, provided a strong theme of communication and transparency in dealing with potential reductions to light. Consequently, the judge held that the developer had not acted “unfairly, exploitative[ly] or covertly”.

Such positive conduct meant the developer was in a strong position to argue that an injunction would be oppressive, and the judge noted that the developer was entitled to advance the points of futility, waste of resources, oppression and public harm as reasons for refusing an injunction. The developer’s conduct here was central to the mitigation of risk and the management of potential claims from neighbouring property owners.

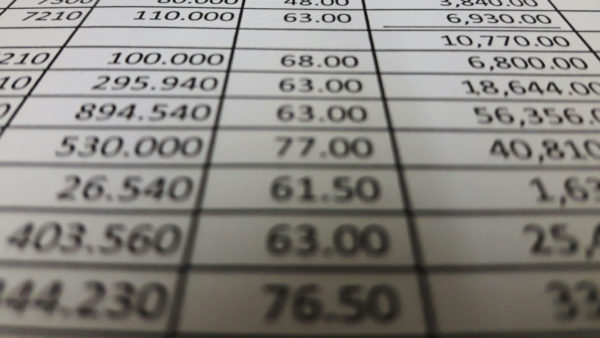

The court also went some way towards recognising developer risk on the question of damages to affected parties. Damages in the Bankside litigation were based on a share of the value the developer gained in being able to build the part of the development which was found to injure the claimants’ rights. In previous cases, the percentage share of profit had reached a third of that attached to the offending part of the building.

Here, the judge was clear that “one-third is not an assumed end point for a negotiation”. The size and complexity of the scheme, the high risk to the developer and the nature of the injury suffered by the claimants, led to a “relatively modest” share of the potential gain being agreed on a hypothetical basis.

The relevant share of the increase in value was considered to be within a range of 10%-15% to reflect developer risk and, hypothetically, the parties were assumed to have settled on 12.5% as an appropriate share. This was then reduced further as the judge reduced the resulting damages to a figure that “feels right”.

By our calculations, this in effect gave the claimants an apportioned share of 8.5% of the uplift in value to the developer from the offending part of the development.

Where does this leave developers?

Navigating the rights to light enjoyed by neighbouring property owners is a potential minefield, but the risks can be mitigated through early analysis and proactive engagement, along with early consideration of risk mitigation tools, such as a light obstruction notice, statutory appropriation (under Section 203) if relevant, and indemnity insurance.

We all knew that the courts would not condone poor developer behaviour, but this judgment goes a long way in outlining what ‘good’ looks like and provides a guide for developers and their advisers to meet and exceed in managing rights to light risk as part of the wider challenge in delivering urban development.

There is a welcome realism in some aspects of the court’s decision, which balances the need for urban development with the almost inevitable impact on individuals’ rights.

Rachel Kerr and Nicholas Levy are partners at Trowers & Hamlins.