Construction’s great strength is its ability to adapt, but it needs better strategic direction from government to deliver on policy promises, writes Brian Green, author of an upcoming CIOB report.

Construction changes our environment not just for centuries, but millennia. Even today in Britain, we drive on roads first laid by Romans.

Yet, while construction as an industry and producer of the built environment craves and thrives on stability and a long-term strategic direction, it is trapped in a political, institutional and economic framework that is not just short term in outlook, but fickle, volatile and constantly in conflict.

This fickle, volatile, conflicted ecosystem has undoubtedly greatly influenced construction’s evolution. Sadly, the consensus from multiple reports over many decades suggests it has evolved into a dysfunctional industry.

That view provides no comfort as the nation faces a period when it must fundamentally reshape the built environment. The impact of demographic change and digitalisation and the need to decarbonise the economy point to profound changes ahead in where and how we live, work, shop and socialise.

If Britain is to flourish it requires a renaissance in its built and natural environment on a scale not seen since the end of the second world war. This raises tricky questions over the industry’s capacity to deliver what is needed. It is these questions that provide the focus for an upcoming report published by CIOB.

Looking back through an ever-expanding library of reports into construction, the list of intractable problems ranges from lack of innovation and poor productivity to low quality, poor value and high levels of conflict… the list goes on. The emphases may vary, report to report, but the catalogue of failings is familiar, even today.

Focus on causes

Many of these reports offered up familiar prescriptions, from contractual reform and partnering, to innovation and prefabrication, to skills and image. But the taint of dysfunction lingers. In reality, the patient has improved but sadly remains sick. That certainly is a common view.

This suggests that rather than pursuing prescriptions to fix the symptoms we should turn greater attention to the causes. If it is the political, institutional and economic framework that caused the dysfunction, surely that should in our sights. This is the tack taken in the new CIOB report.

It states: “Central to this report is the belief that much of the construction sector’s dysfunction is down to the environment within which it operates, one of high volatility and uncertainty. This has led to excessive fragmentation and too often a destructive allocation of risk.

“If we are serious about encouraging long-term positive change, we need to appreciate this. Changing the business environment inevitably changes how firms behave. The task is to work out what changes to the business environment will encourage positive change.”

The report highlights three critical interlinked areas well worth exploring. These are: efforts to reduce volatility; an acceleration in progress toward a robust and coherent institutional framework within which the sector operates; and significant advance in the quality and depth of information available.

It graphically reveals the extreme volatility the industry faces, more than all other sectors of the economy bar the extraction industries. At local levels its volatility is more extreme. This heavily influences how the construction sector forms. It intensifies the struggle to recruit, it limits investment, and it increases the number of company failures. And it induces conflict into relationships between firms.

Public sector investment

Importantly, the report highlights how the public sector compounds the problem by commissioning work when the economy is buoyant and tax revenues high. This is when private sector investment also peaks. Government has the power to smooth the flow of construction work by more considered public spending. But it seems unable to do so.

One potential reason is the lack of a non-partisan long-term strategic framework for the built environment and the lack of a suitable body that can provide one. How, when, where and if we invest in construction becomes competitive, not just in the private sector, but between political parties and the multitude of actors involved in the institutional framework.

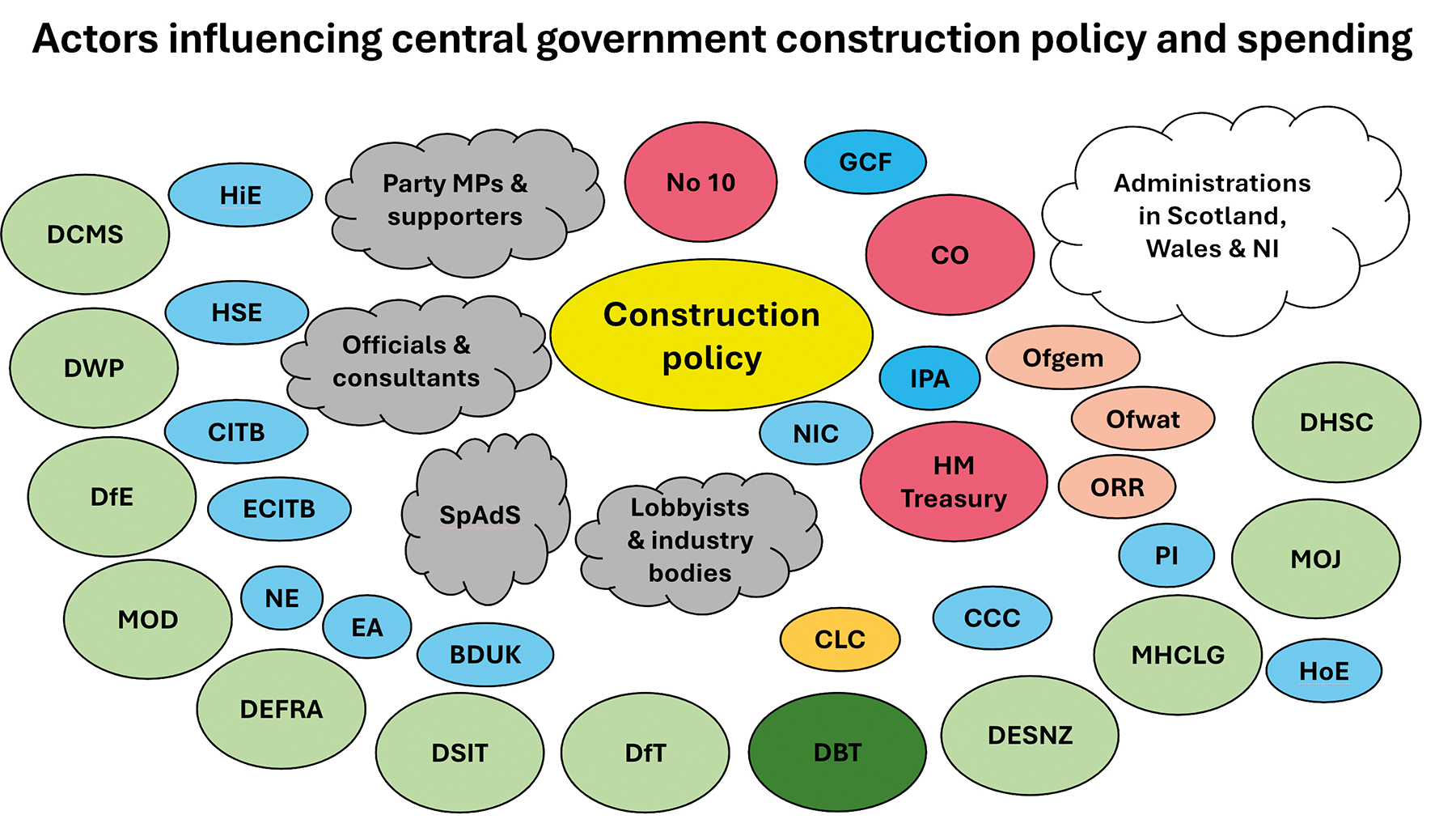

The report offers up a schema highlighting the complexity of the current system that governs the sector, revealing a plethora of government departments, non-governmental organisations, and other interest groups that influence how we shape the built and natural environment (see chart below).

Not only is there an absence of any well-resourced coordinating body for the built environment, but, quite rightly, multiple organisations engaged in the system have clearly competing interests.

This poses the obvious question: Don’t we need a body with sufficient authority and a deep understanding of the natural and built environment that can take account of the competing interests of stakeholders and formulate sage strategic long‑term advice and guidance?

A step in the right direction

The lack of long-term thinking and a suitable institutional structure for delivering the built environment is gradually being recognised in political circles, the report says. It cites the fusing of the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) with the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) to form the National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority (NISTA) as a step in this direction.

But it calls for expanding the remit and for greater independence, which it argues would support and improve government decision-making. It says: “The creation of an oversight body independent of government for the built and natural environment would increase its legitimacy. This is of particular importance when its recommendations might result in political discord.”

The need for such a body links with the need for improved information. It says: “In line with the expansion of the remit of a NISTA-type body, as recommended above, there is a powerful case for such a body to embrace a knowledge hub that would include a dynamic spatial database of projects, a comprehensive set of market data, and a knowledge hub for innovations.”

Arguably, while the tools to order and manipulate data are more powerful and available today, the quality of much of the data describing construction is worse. With the modern economy becoming more complex, it is getting tougher for the government to understand the workings of the construction sector.

This creates naivety within political circles and leads to poor policymaking. For instance, years before Keir Starmer made his 1.5 million new homes pledge in October 2023 there was sufficient evidence to suggest it was unachievable, if it relied solely on private sector sales. The government has now faced embarrassment and a hit to its credibility with a parliamentary committee chair making this point in an open letter to the chancellor of the exchequer.

No quick fix

Changing the environment will not solve all the woes of the industry, nor for that matter political embarrassments. But the report does point out that taking an evolutionary approach does play to the industry’s well-recognised strength: its ability to adapt.

Furthermore, the report recognises that even if there is consensus on this approach, it offers no quick fix. Short-term measures will also need to be in the mix if the construction sector is to have the capacity and capabilities to take on the huge challenges ahead.

Brian Green is a construction analyst and commentator.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Over the last 40 or so years the leaders of the UK construction industry have failed to challenge the neoliberal economic and political thinking that has led to short-termism and lack of stability through its insistence on ‘fiscal rules’ which make no sense in an economy where the government issues its own currency and is self-financing (as the Bank of England accepts is the case). If they want stability they (and we all) need to challenge this fake economics. The change to the fiscal rules which affect capital spending may go a little way to providing a bit more stability but not enough – the whole ‘fiscal rule’ thing is based on falsehoods and needs to challenged – otherwise the past will be repeated in an endless loop.